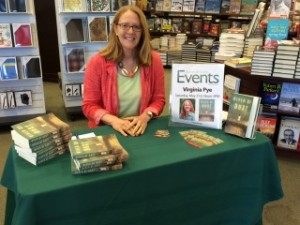

It’s real work running an active blog and I admire Bill Wolfe for the job he's doing on his site, Read Her Like An Open Book. His premise is simple: he reads and reviews only books by women authors. In some cases, he interviews the authors, or asks them to contribute their own short essays. I was delighted when he asked to interview me and was also super pleased with his review of River of Dust as well! I hope you'll link to it and enjoy his wise reading. But, here I'll share the interview, which I thoroughly enjoyed doing with him: Virginia Pye’s debut novel, River of Dust, was published last year to acclaim by critics and fellow writers. Inspired by her grandfather’s missionary work in early 20th century China, Pye transformed his journals into a compelling story of a young missionary couple whose child is kidnapped by Mongol nomads and the life-altering effect it has on them. River of Dust was published in paperback by Unbridled Books on April 15.

BF: You’ve been writing for quite a while, but River of Dust is your first published novel. Was that intentional? By which I mean, were you primarily a short story writer and then decided to write a novel? Or did you write some novels which, for one reason or another, remain unpublished?

VP: I have to admit that I laughed out loud at your first question, Bill. Here’s the short answer: no, it wasn’t intentional to write five unpublished novels before River of Dust.

But, strangely enough, now I’m almost glad that my writing career has transpired this way. I came out of the Sarah Lawrence MFA program with a novel to sell, and an excellent literary agent tried her best with it. Then, over the years, another excellent literary agent tried to sell several other novels. As often happens, the timing wasn’t right—either the market or the work wasn’t ready. Had the stars aligned and some of my earlier novels been published, I’m sure I would have been proud of them, but in the end, I think River of Dust is more accomplished than any of the earlier books because I learned a lot by writing them.

I wrote short stories all along as well, and sent them off to literary magazines where some were taken. By the way, if you’re aiming high, short stories are as difficult to place as getting a book published.

I actually ended up writing River of Dust in a very short period of time, because I’d been thinking about the ideas behind it for years, and because, as I said, I’d gotten better at novel-writing through practice. The earlier books took years, but River of Dust was written in a burst of energy and was a breeze by comparison. Something clicked, and I dove right in and let the fast-paced story carry me forward. It was more fun to write than anything I’d ever done before, because I’d gained enough confidence to really let my imagination take flight.

BF: Tell me about the inspiration for River of Dust. I know your grandfather was a missionary in China and your father was born there. What fascinates you about China and the missionaries’ work there?

VP: Growing up, I tried to avoid thinking about my family’s missionary background. I didn’t want to claim it in any way because, as someone who came of age at the end of the Vietnam War, I understood the destructiveness of American imperialism. And yet, China was in my background. Two generations of our family had lived there and I lived in Hong Kong for a short while when I was very young. I also grew up in a house filled with Chinese furniture and art. As a kid, I would gaze into sepia-toned photos of my grandfather seated on mule back on that arid Chinese plain, or my grandmother surrounded by Chinese children in a dusty courtyard. Who were those white people, I wondered, and how on earth did they think they belonged in that strange, other world?

Years later, when my parents moved out of the house where I grew up, I took it upon myself to cart my grandfather’s papers back to my home in Richmond, Virginia. I started to read his journals and his reports to the American missionary board. Mixed in with his calculations of costs for supplies and lists of recent converts, were also his descriptions of the setting and the people. It turned out that he wrote beautifully, even poetically, about the Chinese landscape and those who lived there. I started to enjoy his wry humor and fluid prose, and although his sense of superiority was apparent, it was also clear that he genuinely admired the Chinese.

My earlier, unpublished novels tended to revolve around American women of various ages who, over the course of their dramatic tales, wrestled with what it meant to be privileged. Those stories dealt with the ways that racism and classism separates people; they asked how can we ever reach across and make a real difference to anyone?

As I read my grandfather’s journals, I realized that he, too, had wrestled with such questions. As a person of privilege—which, incidentally, all white people are in one way or another—how do you reconcile your advantages in a world that is harsh and cruel to so many? In other words, how can we be truly good, not just appear so?

The missionary setting insists that white characters face those kinds of issues. Because I’d grown up with China in my consciousness, it felt familiar—although I’d never been to the mainland until earlier this spring, after River of Dust was published. But the province where my grandparents and father had once lived in northwestern China seemed like a logical place to set my story.

BF: River of Dust seems to be many books in one. It’s a suspense novel about a parent’s search for a kidnapped child, a character study of a clergyman having a crisis of faith, a travelogue of sorts about Americans in rural China circa 1910, a fish out of water story, and an examination of a young marriage. How did you manage to combine all these threads into one seamless story?

VP: My first goal was to write an engaging story—one that had a plot and some intrigue to keep the reader involved. But I love character and try to explore ideas through character. What makes this literary fiction and not, say, highly commercial or genre fiction, is that larger ideas and themes are woven into the story. My goal was to make those different elements seamless, so thank you for that compliment. I wouldn’t have been happy writing just a good story, or a simple character study. And I certainly wasn’t interested in writing a treatise on issues of race, or something like that. The fiction I admire tries to meld all those elements together.

I wanted the Reverend to be a witty character—intentionally or unintentionally—and someone who faces a true crisis of conscience.

BF: Reverend Watson is a good man, but he is prone to tunnel vision and susceptible to many of the temptations that pose a threat to lesser men. I found his spiritual crisis and ensuing journey to be a compelling story. What was your intention with this aspect of the novel? What makes the Reverend tick?

VP: I wanted the Reverend to be a witty character—intentionally or unintentionally—and someone who faces a true crisis of conscience. I think his creation was most directly influenced by the colonial literature I’ve read over the years: Maugham’s The Painted Veil or Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King, both novels that I love, which show male characters flawed by hubris. You could say that the Reverend ends up illustrating the downfall of the white man, though hopefully his travails are individualized and unique.

BF: As the Reverend’s wife, Grace is an effective foil: domestic while he is adventurous, emotional while he is intellectual, a young soul to his old soul, physically weak and often ill while he is a larger-than-life presence. And yet she turns out to be more than she (and the reader) first suspects. Can you talk about what you were exploring in her character and in her marriage?

VP: I think of Grace as a naïve ingénue at the start of the novel. As a girl of that era and class, she was not raised to deal with the harshness of reality—especially not the realities of the rough landscape where she winds up. But the more difficult her story becomes, the more she must reach down into her soul and find strength. Today, a young girl is expected to grow up and support herself, but back then, it was more routinely assumed that a woman would be taken care of. This story shows what happens when a girl with that type of upbringing must learn to finally make her own way in the world and the difficult decisions she must face.

I let my imagination go and decided not to try to set my story in a real place, but instead created an allegorical China.

BF: The characters of Mai Lin, Grace’s “lady-in-waiting,” and Ahcho, the Reverend’s man, nearly steal the story. I enjoyed the way in which they represented the Chinese people, yet were not alike. Describe the important roles they play in the book.

VP: I didn’t want to presume to be able to tell the full stories of the Chinese characters, but thought that their perspectives were needed to reveal the naiveté and ignorance of the Americans. Ahcho and Mai Lin have a better sense of what is going on around them than their American employers. Gleaning a hint of their broader understanding of their country helps the reader to realize that the Americans don’t know the full story. That the two main Chinese characters have such different perspectives from each other adds another layer of understanding for the reader, I hope, and underlines the concept that there are no definitive answers to the questions posed by the story.

BF: How did you manage to capture such a strong sense of place despite never having traveled to China?

VP: I’m not sure, except that I did look closely at those old China photos, and I read my grandfather’s journals, and recalled some of my father’s childhood stories. But mostly, I let my imagination go and decided not to try to set my story in a real place, but instead created an allegorical China—one that exists only in my mind and now on the page. Once I gave myself permission to not stick closely to research or aim for precise imitation, I could then create a harsh landscape that serves as a main character in the novel.

I tend to be able to write for hours and have to make myself stop and take breaks.

BF: When the Reverend arrives in China, he finds that some Chinese have adopted the new faith, but most people are uninterested, highly skeptical, or even hostile to this strange religion and those who have come from America to spread it They are faced with more pressing, life or death matters. This aspect of the plot forces the reader to consider both forms of faith in a new way, particularly to look at Christianity from the eyes of a non-Christian/non-monotheist. How did you get into the mind of an early 20th century Chinese peasant and capture their worldview so well?

VP: It wasn’t difficult for me to imagine a skeptical response to these foreign missionaries. I think that came fairly naturally. I’m not sure how I managed to translate that into the Chinese characters, but I did. What was harder for me was conveying the true beliefs of the Reverend. My grandfather writes in his journals as a zealot: he proudly shares his list of converts on any given day or month. The conviction of his beliefs is much harder for me to imagine, whereas the non-believers I somehow instinctively understand.

BF: I was pleased to see Grace develop into someone who was more than just a dutiful wife, dying for her husband’s attention and approval. Without giving anything away, what motivated you to have her grow in this way? Were you concerned that some readers might find this evolution too modern for the time and place (despite the fact that history is full of examples of women like Grace)?

VP: I think her story is believable: some girls in all eras have been raised to not consider themselves capable in the world, particularly girls raised with privilege who are kept in a “gilded cage.” The story of girls growing stronger as they face hardship is not uncommon in literature. Madame Bovary, for example, wanted to live in the precious world of her romance stories, but Flaubert makes her literally trudge through mud to show how real her world truly is and how she must contend with it.

BF: What are you working on now?

VP: I recently completed a new novel set in China in 1937. It tells the story of an American woman and her teenage son living there right at the moment when the Japanese occupation turns to actual war. The mother is not someone well prepared to deal with it, but deal with it she must! She winds up with the Communists and even manages to meet their leader. As the situation around them grows more dangerous and violent, the reader wonders if she and her son will get out of that warring country alive.

I’m also completing a collection of short stories that I’ve been working on for literally decades. My stories accumulate slowly and I finally realized that I have enough for a collection, so that’s what I’m working on right now.

I read all the time, often more than one novel at once, and I especially focus on contemporary fiction.

BF: What is your writing routine? Where do you usually work, when, how, etc.?

VP: I write pretty much every day, usually in the morning, though sometimes I’ll grab a free minute later in the day. The last few years have been very productive for me. I have several projects going at once and have no problem finding the energy or focus to write, so I just jump in each day. I’ve gotten in the habit of lighting a good-smelling candle before I start to write and the sound of it sputtering and the sight of it flickering provides me with some company and nice energy. I tend to be able to write for hours and have to make myself stop and take breaks. I’m pretty immersed these days.

BF: What have you read recently that impressed you? What are you reading at the moment?

VP: I read all the time, often more than one novel at once, and I especially focus on contemporary fiction. I just finished Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings, which I really loved and admired. That’s a book I wish I had written, probably because its characters felt so familiar to me. Now I’m reading Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World. I like novels about art and artists. Several artist and art collector friends and I have recently started an impromptu book club to read novels exclusively about art and artists. We started with The Goldfinch, then read Rachel Kushner’sThe Flamethrowers. I’m not sure how long we’ll keep this up, but it’s a very fun way to bring together art and literature.

Other books recently read: The End of the Point by Elizabeth Graver; The Whiskey Baron by Jon Sealy; The Lighthouse Road by Peter Geye; Bones of the Inland Sea by Mary Akers; Man, Alive! by Mary Kay Zuravleff; The Geometry of Love by Jessica Levine; A Different Son by Elaine Neil Orr; Out of Peel Street by Laura Long. All of these, I realize with true delight, are by new friends—fellow writers I’ve met through the process of having a book published. I might just like that aspect of sharing my work best of all.

Related

River of Dust: A Spiritual Journey Through Unknown China for Characters and Readers Alike

Blau, Levitt and Pye Stand Out in SheBooks' Mini e-Book Offerings

Shebooks to Publish Short e-Books by Women Authors

Leave a comment

Filed under Author Interviews

Tagged as China, Chinese history, colonialism,contemporary fiction, crisis of faith, debut novel, Donna Tartt,imperialism, literary fiction, meg wolitzer, missionaries, novels, Rachel Kushner, River of Dust, Siri Hustvedt, The Blazing World, The Flamethrowers, The Goldfinch, The Interestings, Virginia Pye, Writers

Michele Young-Stone’s first novel, The Handbook for Lightening Strike Survivors established her as a new and distinct voice in American letters. Her second novel, Above Us Only Sky, is now out and is every bit as original, heartfelt and lovingly written as her first. It is a magical novel about a family of women separated by oceans, generations, and war, but connected by something much greater—the gift of wings. Both novels offer whimsical, imaginative stories that balance danger and the dark side of life with an uplifting spirit. Lydia Netzer, author of the Shine, Shine, Shine and How to Tell Toledo from the Night Sky, has called, Above Us Only Sky “...a raw, beautiful, unforgettable book that folds unfathomable horrors and unfathomable love into a story of incredible power."

I've had the pleasure of getting to know Michele when we were neighbors in Richmond. When her first novel came out, I interviewed her, her editor, and her agent at a James River Writers event. Michele has a sparkle to her that is evident in person and on every page she writes. I'm delighted to interview her here.

Michele Young-Stone’s first novel, The Handbook for Lightening Strike Survivors established her as a new and distinct voice in American letters. Her second novel, Above Us Only Sky, is now out and is every bit as original, heartfelt and lovingly written as her first. It is a magical novel about a family of women separated by oceans, generations, and war, but connected by something much greater—the gift of wings. Both novels offer whimsical, imaginative stories that balance danger and the dark side of life with an uplifting spirit. Lydia Netzer, author of the Shine, Shine, Shine and How to Tell Toledo from the Night Sky, has called, Above Us Only Sky “...a raw, beautiful, unforgettable book that folds unfathomable horrors and unfathomable love into a story of incredible power."

I've had the pleasure of getting to know Michele when we were neighbors in Richmond. When her first novel came out, I interviewed her, her editor, and her agent at a James River Writers event. Michele has a sparkle to her that is evident in person and on every page she writes. I'm delighted to interview her here. MYS: It’s also a YA novel! I don’t mind labels. I don’t think about them. I write my books and let marketing folks label them as they see fit. I think I’ll always fall under the umbrella of magical realism because I see the world in a magical way. I recently realized that magical realism is nothing more than perception. When I was a kid, I had an imaginary friend named Booby; he lived in the train station in Crewe, Virginia. I also used to cook for the queen of England. Imagination is everything in fiction. My life is magical. I feel God when I’m by the ocean, and I live by the sea. When I write, I impart my worldview.

MYS: It’s also a YA novel! I don’t mind labels. I don’t think about them. I write my books and let marketing folks label them as they see fit. I think I’ll always fall under the umbrella of magical realism because I see the world in a magical way. I recently realized that magical realism is nothing more than perception. When I was a kid, I had an imaginary friend named Booby; he lived in the train station in Crewe, Virginia. I also used to cook for the queen of England. Imagination is everything in fiction. My life is magical. I feel God when I’m by the ocean, and I live by the sea. When I write, I impart my worldview.

"In making your mind up on these issues," McEwan said, "I hope you’ll remember your time at Dickinson and the novels you may have read here. It would prompt you, I hope, in the direction of mental freedom. The novel as a literary form was born out of the Enlightenment, out of curiosity about and respect for the individual. Its traditions impel it towards pluralism, openness, a sympathetic desire to inhabit the minds of others. There is no man, woman or child, on earth whose mind the novel cannot reconstruct. Totalitarian systems are right with regard to their narrow interests when they lock up novelists. The novel is, or can be, the ultimate expression of free speech."

"In making your mind up on these issues," McEwan said, "I hope you’ll remember your time at Dickinson and the novels you may have read here. It would prompt you, I hope, in the direction of mental freedom. The novel as a literary form was born out of the Enlightenment, out of curiosity about and respect for the individual. Its traditions impel it towards pluralism, openness, a sympathetic desire to inhabit the minds of others. There is no man, woman or child, on earth whose mind the novel cannot reconstruct. Totalitarian systems are right with regard to their narrow interests when they lock up novelists. The novel is, or can be, the ultimate expression of free speech."

VP: At the upcoming

VP: At the upcoming

KC: The structure evolved from the story. My first draft was a linear first-person narrative from Addie’s point of view. When I began to revise, I realized first-person didn’t work: Addie

doesn’t know enough to tell the whole story. So I—gulp—started over, writing from every point of view I could think of. At the same time, I didn’t want to lose the intimacy of first person; I wanted to keep Addie’s voice—which I did through her letters to Byrd, her absent son. The book ended up with a fairly intricate structure, but it worked, at least for me. It gave me access to the whole story. And, as you say, it also led me to think more about missed connections and missed opportunities and the slipperiness of memory and just how little people actually know about each other.

KC: The structure evolved from the story. My first draft was a linear first-person narrative from Addie’s point of view. When I began to revise, I realized first-person didn’t work: Addie

doesn’t know enough to tell the whole story. So I—gulp—started over, writing from every point of view I could think of. At the same time, I didn’t want to lose the intimacy of first person; I wanted to keep Addie’s voice—which I did through her letters to Byrd, her absent son. The book ended up with a fairly intricate structure, but it worked, at least for me. It gave me access to the whole story. And, as you say, it also led me to think more about missed connections and missed opportunities and the slipperiness of memory and just how little people actually know about each other.

KL-M: I just get up every day and do the best I can to move my stories along. Sometimes I write a few sentences. Sometimes I just take notes. But I’m always, always trying to kick the ball down the road a little further each day. Some days it’s simply not possible—like over the summer, when everyone is home from school. I suppose my superpower is being able to work in short snatches and still hold the thread of a story together.

KL-M: I just get up every day and do the best I can to move my stories along. Sometimes I write a few sentences. Sometimes I just take notes. But I’m always, always trying to kick the ball down the road a little further each day. Some days it’s simply not possible—like over the summer, when everyone is home from school. I suppose my superpower is being able to work in short snatches and still hold the thread of a story together.