Interviews

TV | Radio | Web

Writing Historical Fiction with authors Virginia Pye and Whitney Scharer

Brattleboro Literary Festival

New Novel Shows the Journey of a Woman Who Sues Her Boston Publisher for Back Wages

WBUR Boston

Ep 167: Virginia Pye on the Literary Women of Gilded Age Boston

A Bookish Home Podcast

An Interview with Virginia Pye

Inside the Writer’s Studio

Award-winning author Virginia Pye introduced her latest work, Dreams of the Red Phoenix

WTVR | Virginia This Morning

WTVR-CBS Interviews Virginia Pye

WTVR-CBS

Sunday Evening Lecture: Dreams of the Red Phoenix with Virginia Pye

Stonington Free Library Lecture

Interview 32: Virginia Pye

The Outrider

Print | Digital

Author Interview: Marriage and Other Monuments

Hasty Book List

A Female Writer in Gilded Age Boston Struggles to Be Heard

Boston Globe

Mrs Swann Wants Her Own Way

Richmond Magazine

Late Bloomer: Author Virginia Pye returns to James River Writers with The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann

Richmond Magazine

An Interview with Virginia Pye

The Lit Pub

Shelf Life of Happiness Explores Complexities of Love

Ellen Birkett Review

Virginia Pye, Shelf Life of Happiness

Work-in-Progress

Q&A with Virginia Pye,

Author of Shelf Life of Happiness

Christi Craig

Q&A with Virginia Pye

Book Q&As with Deborah Kalb

Book Chat: Virginia Pye Talks About Her New Book, Shelf Life of Happiness

Read Her Like an Open Book

An Interview with Virginia Pye

Fiction Writers Review

An Interview with Virginia Pye,

Author of Shelf Life of Happiness

Dead Darlings

Hearts in Reserve: Virginia Pye on Shelf Life of Happiness

Grist Journal

An Interview with Novelist Virginia Pye

Kenyon Review: Part I

WTVR-CBS Interviews Virginia Pye

Kenyon Review: Part II

A Story as Big as China

Richmond Magazine

Other Interviews

Book Q&As with Deborah Kalb

Leavittville Blog (DOTR)

Manifest-Station Interview

China Daily

Huffington Post

Washington Independent Review of Books

Sampan

Fiction Writers Review

Leavittville Blog (ROD)

HastY Book List

Author Interview: Marriage and Other Monuments

Ashley Hasty | February 7, 2026

Marriage and Other Monuments is set in Richmond, Virginia, during the tumultuous summer of 2020. It tells the story of two estranged sisters whose marriages implode against the backdrop of the social justice protests and the removal of Confederate monuments. The experience brings them closer, while their husbands conspire in a racial reckoning their ancestors would never have dreamed of. The story was inspired by the real/actual events of that summer and by what it takes to have a successful multi-decade marriage, built on a foundation of give and take that encourages evolution, as individuals and as a couple, even in challenging times.

Author I draw inspiration from:

Tessa Hadley comes to mind. I love her novels and also her wonderful short stories. But I’m choosing a different British woman author: Penelope Lively. I love her novels. She writes with humor and cleverness about regular people—couples and families facing common problems but each unique and artfully drawn. Her characters are such good souls who get themselves into such terrible messes. My favorite novel of hers is Consequences. It’s a slim novel that still manages to tell a very full and detailed love story over three generations of women against the backdrop of major events of the twentieth century. It’s miraculous how she picks key moments, that are also everyday moments, that somehow convey whole lifetimes. And I love the settings! Who can’t fall in love with a country cottage in the English landscape. I highly recommend Penelope Lively’s many books!

-

Favorite place to read a book:

In the early morning hours, as daylight is just filling the windows of my living room, I love to sit on the sofa with a captivating book, a cup of green tea, and my mini-poodle, Honey, curled up and fast asleep on my lap.Book character I’d like to be stuck in an elevator with:

I’d love to be in an elevator with all of Elizabeth Strout’s main characters—Olive Kitteridge and Lucky Barton and the rest, though, I have to admit, I wouldn’t fit in at all with them. Same with the characters in Christopher Tilghman’s four novels set on the Eastern Shore of Maryland over many generations. I’d love to be with Thomas and Beal in the Midi in France, but again, I’d stand out like a sore thumb.But to be in an elevator with one character is even harder to imagine. Yet, what if I could somehow whisper into Madame Bovary’s ear to help her avoid her fate? Maybe I could convince her to read books other than the silly romances that led her astray. Or, what if I could stand beside Anna Karenina and get through to her that her lover Vronsky is no good for her. Instead, I would speak of the more noble character of Levin and others. But it’s no good. Neither of them would change. They are who they are, and I’d have to get off at my floor, having changed nothing. Those indelible storylines are what they are forever.

The moment I knew I wanted to become an author:

At age ten, as I stood beside my mother as she prepared dinner at the stove, I recited a poem I had written about the snow falling outside. The poem was pretty heavy-handed in its imagery. It was about how the snowflakes that had fallen on the poet’s hand were melting now that she/I had come indoors. The “life” of the snowflake was compared in the poem to the life of a person. Short and sweet. It was a first metaphor and I loved it!Hardback, paperback, ebook or audiobook:

I love to hold and admire hardbacks, but I love to read from paperbacks. They’re easier on the hands and wrists, especially when reading in bed. I listen to audiobooks all the time as I’m doing household tasks or driving. For audiobooks, I try to choose books that are plot driven and not as focused on language. Ones that I’m swept along in what happens next. For novels that are more precise in their language and characterizations, I prefer to read from actual books.The last book I read:

Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust is absolutely brilliant, but that’s no great surprise. The author of Brideshead Revisited and other classics, he’s a fantastic storyteller and creator of characters. In this one, he creates characters who have too much and are bored with their stature. Through truly terrible life choices they bit by bit loose everything. Where they land in the end is comical, yet tragic, like so much of Waugh’s work.Pen and paper or computer:

I write at my desktop Mac in the mornings. When I’m at work on a novel or short story, I sometimes wake as early as four am and go to my desk because my mind is buzzing with the work. Lots of ideas come to me in my sleep—not fully formed, but more as a feeling of inspiration. If I get to my desk with that buzz, I can often have a great breakthrough, writing a scene or conceiving of some important moment in the story I’m writing.Book character I think I’d be best friends with:

I find this question really hard, as I did the question about the elevator. I think I don’t think of characters as people. I mean, as I read, I let my imagination be taken wherever the writer wants it to go. I don’t hold back as a reader. But I also don’t think of the characters as anything other than creations. It’s probably because I create characters myself, so I’m always looks for the ingredients that have gone into the making of people on the page.If I weren’t an author, I’d be a:

As dull as it sounds, I’d probably go back to teaching writing. Although...I’m also very much a people person and sometimes I think I wish I’d gone into, gulp!, politics. That is, politics on a local level and as it used to be practiced, with constituents and pols working together to improve a neighborhood or city. Then again, I could also see myself as a caregiver to the elderly. Or small children. I guess I could do a number of things!Favorite decade in fashion history:

Turn of the twentieth century, before the flappers and after the high formalism of the Victoria era. Some women, like Virginia Wolfe, had started to wear pants. And I love those shoes she wore that look like men’s wingtips. I never wear those now, though I could. They just seem to belong in another time and place.Place I’d most like to travel:

My husband and I return to Italy often, exploring different regions. As Stanley Tucci proved, each part of Italy is different from anywhere else, with different food and landscape and customs. It’s like going to an altogether different county, but since my husband has taught himself Italian, we manage well throughout.My signature drink:

I love jasmine green tea with honey. And I love rose in warmer weather. But not together. One is more daytime and other for evening. You can guess which is which!Favorite artist:

Oh dear, here’s where I have another problem: my husband of forty years is a longtime contemporary art curator and for almost half a century we’ve visited museums wherever we go. I have seen SO MUCH ART! And I often known what I love when I see it, but honestly, I feel like every painting and sculpture is part of a larger conversation that are all mixed up in my mind with references to other works. I’m often blown away by a Rembrandt or a Matisse or a Kara Walker or William Kentridge.Number one on my bucket list:

We’re going to Australia soon for our daughter’s wedding to an Australian man of Indian background, where we’ll be part of a five-day Indian wedding. I think that’s pretty great, since we love these kids and enjoy his family. I can’t wait to be welcomed into that foreign land by these lovely people!Anything else you’d like to add:

I hope readers check out my latest novel, Marriage and Other Monuments, which was written from the heart. It’s about marriage and how times of dramatic change can affect us all, even those not involved overtly. It’s a love story to a smaller city, one not without problems, but filled with good people, like every place.

WBUR Boston

New Novel Shows the Journey of a Woman Who Sues Her Boston Publisher for Back Wages

Amanda Beland and Tiziana Dearing | November 16, 2023

Mary Abigail Dodge, known by her pen name Gail Hamilton, was a prominent author in the mid-19th century, including here in Boston.

In 1867, she fought back against her publisher when she discovered she was getting paid less than other authors. Her real life and struggles are the basis of the fiction book called The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann. The book’s author, Virginia Pye, joins Radio Boston to talk about that history and Boston as a city.

Boston Globe

In Virginia Pye’s Novel, a Female Writer in Gilded Age Boston Struggles to Be Heard

Pye, who grew up in Belmont and lives in Cambridge, found inspiration for her character in real-life 19th-century Massachusetts author Mary Abigail Dodge.

Lauren Daley | November 14, 2023

Assumptions about what women readers read, and what women writers write is a central vein of Virginia Pye’s The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann. In the novel, set in Gilded Age Boston, Pye’s protagonist, Victoria Meeks, writes women’s dime novels, and pulpy popular romance for “lady readers,” under the pen name Mrs. Swann. And she’s dissatisfied.

“I place my heroines on tropical shores, in Russian palaces, or deep in the jeweled bowels of Nefertiti’s tomb. The sorts of places where my readers have never been, and … neither have I,” Meeks tells one editor.

She tells another: “[T]hose settings aren’t real. I want to write about women who are made of flesh and bones, with the kinds of problems that my readers might have experienced themselves …”

-

“Ladies don’t want that,” her older male editor tells her.

So she finds an ally in a younger editor, takes a stand, and publishes a novel, under her own name, centered on a character she develops as a real Boston woman.

Pye, who grew up in Belmont, said she thinks of the novel as a “love letter to books” and Boston. I called Pye at her Cambridge home ahead of her November 15 virtual talk and Q&A via Ashland, Wayland, and Tewksbury public libraries.

Boston Globe: You’ve said this book was sparked by your returning to Cambridge and being “struck by the way the city’s bookishness contrasts with other places” you’ve lived.

Pye: Exactly. I was figuring what to write about and kept noticing how people here read so much: on the subway, walking down the street. I saw somebody reading at the stoplight, book up on the steering wheel.

I noticed Boston has a lot of monuments and markers to our literary heritage — particularly to the gentlemen of letters who’ve lived here. I started to feel the shadow of it. I wondered what it would’ve been like to be a woman writer in that earlier time, trying to be heard, be read. What if you didn’t write that high literary kind of writing? What if you wrote, what they would have called back then, frivolous writing for other women?

Then I went to the Schlesinger Library [at the Radcliffe Institute] and came upon “Gail Hamilton,” the pen name for Mary Abigail Dodge who sued [her publisher] for underpaying her. She lost, but the lightbulb went off: There’s a woman who tried to push back against the male literary establishment. That’s how Victoria was born.

Victoria also champions women readers.

In the 1860s and onward, “New Women” were the first American women to live independently. Women had always lived either with their parents, or their husbands. New Women moved to cities, found jobs. This is where dime novels come in. They were supposed to teach young women how to not get in trouble with men, basically. Titles like A Woman in Peril or Marriage Gone Wrong. One after the next are just really bad romance tropes — something’s gone wrong for the woman, a man rescues her. A man gets down on bended knee and proposes while a white dove lands on her shoulder.

But you turn the page, and there are readers’ letters: women describing “MeToo” moments. The [advice] was never: call the police. It was: you need to change your behavior.

Then you turn the page and it’s ads for women’s reproductive [issues]. Contraceptives and abortion were illegal, so ads [were discreet]. So you see the ideal women are being fed, what their real situation is, and the dire situation of their medical needs — I wanted to portray all of that fictionally.

The book includes other timely themes — abortion, immigration, opioid addiction.

Which is crazy, because I didn’t set out to write a book that had this many current connections. But as I was researching, there were obvious abortion parallels.

Then I discovered there were two opium dens in Boston, hidden in plain sight, like the opioid crisis has been for us. That turned up the story of Chinese women brought over to work these opium dens. Chinese women were the first group outlawed in the US via The Page Act of 1875. So it wasn’t: I need to have an immigrant story. It was: Oh my God, here we are again.

Your synopsis says Swann shows how writing and reading “can liberate us.”

It’s so important for people to be aware by reading newspapers and nonfiction. It’s also important that we keep our imaginations alive by reading fiction. There’s this communication that goes on between the writer, the words on the page, and the image that gets created in the reader’s mind that is deeply human and deeply important.

Richmond Magazine

Mrs Swann Wants Her Own Way

Virginia Pye’s latest novel is set in 1899 Boston, but it resonates here and now.

Harry Kollatz Jr | October 4, 2023

Author Virginia Pye returns to Richmond, where she previously lived, with her recently released novel, The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann. She’s participating in the 21st Annual James River Writers Conference, October 6-8 at the Greater Richmond Convention Center, and a public launching of the title from 5:30 to 7 pm on Saturday, October 7, at Reynolds Gallery’s West Main Street location.

Pye’s past works have included novels about revolutionary China and short stories about individuals struggling to find something like happiness. Now, she’s delved into the rich tapestry of Boston’s historic literary life through the perspective of a dime novelist who desires instead the creation of serious work. This is set against a troubled marriage and upheaval in the publishing business that puts her at odds with how much she’s earning as opposed to the male writers.

-

The novel is reminiscent of one of those Merchant-Ivory period films. Except you can fill the cast from your own imagination.

Pye recently spoke with Richmond magazine about her latest literary creation.

Richmond magazine: This seems to be a departure, at least in terms of setting, from earlier work. But your novels start with the question “What if?”

Virginia Pye: I was walking around Cambridge [Massachusetts], where I live now, and I kept seeing people reading. They were reading on the subways, park benches; I saw people walking down the street while reading books. Books, not their phones — which is wonderful. ... Then I started noticing houses with plaques, and they weren’t to war heroes, and they weren’t to captains of industry, they were for authors. Cambridge is a delightfully bookish town.

I started to wonder what it would be like to be a woman living in this historical setting. I started reading books set in the period, I enjoyed Henry James’ “The Bostonians,” Edith Wharton, though she’s a bit after Victoria, and started reading nonfiction about women writers. Though she was earlier but inspirational, Margaret Fuller, and Louisa May Alcott.

I watched movies set in that era with those expectations of “The Gilded Age.” At the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe college, I stumbled on really only a few lines about Gail Hamilton, which was the nom de plume of Mary Abigail Dodge. In 1867 she sued her publisher Ticknor and Fields for deliberately underpaying her. And that’s all I read about it. In the end, I’m a fiction writer, not a historian.

The cultural threads running through the story include issues familiar to us more than a century on, though now we may have different terms for these concerns: sexual identity and agency, and among issues of pay equity, drug addiction, race and class, freedom of speech and censorship, and women’s reproductive rights.

The novel takes place in 1899, so right on the cusp of a new century. That makes for an interesting moment, I think. In the minds of the characters, they see themselves as being forced into modernity — some embrace [it], and others try to hold it back.

When I was starting on my research, I found in the Brandeis University Library a treasure trove of dime novels with these sentimental stories full of moralizing about women who come in from the farms to live in the cities and what trouble may befall them if they’re not careful. In the back of these books are letters from real women who describe in different ways how they’d been taken advantage of by men — this was way before the Me Too [movement]. One after another, they’d been groped at work or held late at the office with the expectations of sex by their male boss. The advice was always, “Leave the job,” with no notion that you could fight it. If you turn the page, at the back of the dime novels are advertisements including for thinly veiled abortion-related procedures.

Then suddenly, much more recently, after I’d finished the book and it was at the publisher, when the [Texas federal district court decision] came down about the [1873] Comstock Act, my jaw dropped. [Editor’s note: Comstock returned to public view in relation to the mailing of mifepristone.] The Comstock law was used to block anything mailed through the postal service judged as obscene or lascivious. And it was done to, among other things, keep those abortion adverts out of the hands of young women. Also, mention of anything that might refer to what we’d call gay rights, any kind of things perceived as lewd. So, yes. Here we are again.

One aspect of the novel is the celebration of the joy of those hand-held devices known as books and how screens don’t light up but people’s faces do. One can feel a little nostalgic. Yet you can also see a familiarity because people are reading, or bingeing, stories like Victoria Swann’s similar to how we watch streaming serials — which require writers to compose them.

Absolutely, that’s quite deliberate. This is my love story about books, readers and writers, and how incredibly important these are to each other and how it’s a shared society — people who love books and how vital that is to the culture, and so, absolutely, there’s nostalgia, and also a purpose to elevate. I also tried to approach the differentiation between “high” and “low” art and how different people can love a book for their own individual reasons. That’s among the many marvelous characteristics of the relationship between writers and readers.

Style Weekly

Late Bloomer: Author Virginia Pye returns to James River Writers with The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann.

Lorna Wyckoff | October 3, 2023

“It was nothing special to be fearless and intrepid,” the heroine of Virginia Pye’s marvelous new novel, The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann, concludes, but the author could easily be talking about herself. The former Richmonder is in town this week to launch her fourth book to a local literary community that’s been rooting for her since her days here as head of James River Writers.

After years of numerous rejections starting when she was 27, Ginny didn’t publish her first book, River of Dust, until she was 53 years old. Her key strategy in the face of setbacks, she has explained, was to keep writing — not unlike Mrs. Swann, who must persevere as well, in this case as she attempts to find her voice and path following devastating losses at the hands of bad men. Some would call this very fearless and extremely intrepid.

-

There are loads of reasons to love the new book, notably its impressive, meticulous attention to Gilded Age culture, history, costumes and customs. The period comes alive with the appearance of Alice Longfellow on Brattle St.; Martha Washington, lonely and alone before her glory days; the tedious Ladies Book and Travel Club; the popular dime novel; the gentlemen’s club reminiscent of a certain musty male bastion here in town. Ginny gives us an unflinching look at a world chillingly familiar, with banned books (you may recall the Comstock Act that outlawed Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass), back-alley abortions, opium dens and an oppressive, controlling patriarchy, along with gentle reminders about true friendships, honorable work partnerships and the power of purpose.

Look for choice observations like, “How astoundingly delicate oversize men could be,” or, how the manuscript was “dropped in the drawer like a dead body in a shallow grave.”

Style Weekly recently spoke with Pye and the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Style Weekly: Did your thinking about the book begin with a woman in trouble who had to solve something or was this to be a work about book publishing in the Gilded Age?

Virginia Pye: I think it was about that incredible feeling of being in this particular area, of walking around Cambridge, Massachusetts, and feeling the shadows of all these great literary figures. And I saw all these people reading. Reading on the bus. In their cars when they’re at a red light. Reading on the subway. I actually saw someone walking down the street, reading. Who are these people who are reading all the time? It felt different than other places. And where I live are all these historical markers to literary figures, on the homes where they once lived, as a way of honoring them, yet few of them recognize women writers. I started to think about what it might be like to be a woman writing in that era, in the middle of those men, and not necessarily writing the types of things that they were writing.

Did you know Victoria’s life would come crashing down in such a devastating way? It was shocking.

Things happen in books! It’s a funny thing because it’s a book that starts out backwards, first with an internal problem. Victoria wants to be a different kind of writer than she is. She wants to tell her own personal life story, the hardships she faced as a young woman. Instead, she’s being paid a lot of money and her publisher and husband are counting on her to write these adventure novels, these romance novels that she’s getting sick of writing. That’s not exciting, it’s an internal problem, and you can’t dramatize that, so how do you take something that’s happening in in someone’s mind and turn it into something dramatic? I had to figure out how a personal decision would make a life go haywire.

This is an obvious question but are you and Victoria very similar? You must have related to her on a number of levels.

I did, I did. I’ve never written a story about a writer before. I never indulged in that and I feel like maybe every writer gets to do that once — but shouldn’t make a habit of it. This is a story about someone where the arc of their life is intimately tied to the arc of their writing life. The path she takes in life is dictated by what she ends up writing. And I love that idea, that the two are intertwined. That resonates with me because that’s how it’s been in my life. It is my attempt to try to show the portrait of a woman as a maturing writer.

Your story as a published author is pretty remarkable. A lot of people would have given up at age 40. Maybe age 50.

I had my first agent at 27 and my debut novel was five books and three agents later, at age 53, and then I published four books in the ten years since. The dam burst, which is awesome. I also raised two kids at that time.

Was Victoria’s treatment by unseemly gentleman-publisher types part of your own experience or is it observational?

I’ve ended up writing a more personal essay than I usually write that’s going to be coming out in Literary Hub about a young writer having some male domination in the household and also being the youngest sibling. There’s an element of this and of a woman finding her voice. She’s up against stiff odds, with the men closest to her underestimating her, trying to take advantage of her. It’s also how women writers were characterized and expected to write then. There are exceptions like Margaret Fuller, but even Louisa May Alcott wrote dime novels to support herself before “Little Women.”

I noticed that the good guys in the book are mainly the gay guys.

Oops.

This is a feminist book.

It’s definitely a feminist book, on a personal level and in terms of the industry and how women have been getting the short end of the stick. It still exists today, although I think younger women have figured it out. Younger women seem to be standing up more than my generation. There are so many battles on so many fronts.

Who were your early feminist heroines?

My sister Lyndy. She’s 10 years older, and was an avowed feminist in the ‘70s. I vividly remember when she took me to see When Colored Girls who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf [a 1976 work of poetic monologues by Ntozake Shange]. I ended up going once with her, once with a friend, and I took my parents. It was a voice that spoke to me. Lyndy introduced me to that.

Author Virginia Pye will be appearing from October 6 through 8 at the James River Writers Conference in the Greater Richmond Convention Center. Go here for more information. And she will be at Reynolds Gallery, 1514 West Main Street on Saturday, October 7, 5:30 pm for a signing.

A Bookish Home Podcast

Ep 167: Virginia Pye on the Literary Women of Gilded Age Boston

Virginia Pye | September 26, 2023

Boston author Virginia Pye discusses The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann, a historical novel which she calls a love letter to books and authors and to the literary city she adores. It came to be as she imagined being a young woman writing books in Boston’s male-dominated publishing industry of the 19th century.

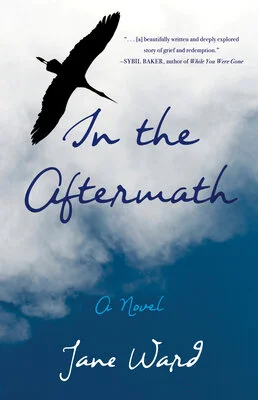

Virginia Pye interviews Jane Ward at the launch of her new book, In the Aftermath, at Belmont Books, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

It’s rare to open a book, read any given page, and find oneself utterly absorbed. But that’s precisely what happened to me as I read Virginia Pye’s marvelous new collection of stories, Shelf Life of Happiness. With supple prose and truly immersive worlds, I found myself neglecting the dishes, my ringing phone, and refusing to turn off the lamp and get to sleep. Pye’s book simply had more meaning and urgency than any of those things.

I met Pye as a fellow writer in Boston where we met at numerous readings, events, and gatherings hosted by GrubStreet, an independent writing center. She immediately struck me as sharp-eyed and generous, and before long I got to share drafts with her in a local writing group. I’m grateful to read her fiction, and to pose some questions to the woman whose work swallowed me up.

Sonya Larson: To me, the great engine of Shelf Life of Happiness is how it juxtaposes life’s tranquil, peaceable, and lovely moments with the dark, sinister, betraying, exploitative, and even murderous. Characters may be attending a theme party, planting flowers in the garden, or vacationing in Italy, but the claws of danger, envy, and manipulation are always on their heels. Do you think about such themes in your work, and how do you manage to have contrasting forces coexist?

-

Virginia Pye: Thanks for that description! I think you’ve captured well the source of tension in these stories. I suppose I think that in the midst of happiness there’s always the possibility of its expiration. That’s what the title of the collection means to suggest. Even knowing that joy can be snatched away, we have to fully throw ourselves into life anyway. In fiction, I’m interested in those moments that teeter on the edge. They allow us to see into the hearts and minds of characters. We figure out who we are when tested by life. The same is true in these stories.

Your book exhibits wonderful range; somehow you’re able to inhabit many different characters from all walks of life—aspiring young skateboarders, aged painters, slick art dealers, wily adulterers, a dying groom, and a town in the aftermath of a family massacre. Where do you get your ideas for these characters, and how did you stretch your imagination to render each one?

I love writing about people I’m not. To me, that’s what fiction is for. Writing gives me an excuse to imagine the inner workings of strangers. A lot has been written recently about how fiction increases empathy in readers and writers, but to me that seems so obvious: art has always been about stretching and enriching our hearts and minds. My characters may be inspired by people I’ve rubbed elbows with, or by people whose situations I’m intrigued by, but then I enlist my imagination to move beyond the real and create new worlds with their own challenges. I think a good story needs a crux—an inner or external conflict—that brings out who characters really are. By putting them in dramatic situations, hopefully they come to a life of their own.

Several of the stories also manage a remarkable feat of craft: they capture a person’s entire life in a tiny, heightened sliver of time. An artist, for example, reflects on a lifetime of longing and regret while struggling to swim. How did you go about writing a short story that’s so ambitious in its scope? Did you begin with that aim in mind?

Usually I know where a story is headed, though I don’t always know how I’ll get there. In the case of Redbone, the story you allude to, I sensed a tragedy, but had to write it to discover how it would unfold. Sometimes, in a story, you need to give the reader an encapsulation of a character’s past. The trick is figuring out how much or how little to share. I think reading and writing a lot of fiction over the years has helped me to make an educated guess. I also think about rhythm in my writing—not wanting to get stuck on one note for too long, or bore the reader, but instead keep a story humming along.

Which story was most fun/most difficult? Which taught you the most as a writer?

My first thought was that there’s only one story, Her Mother’s Garden, that taught me something: it helped me to move on from the grief I felt over my parents’ deaths and the sale of the house where I grew up. But actually, each story in the collection helped me in some unique way. Best Man helped me absorb the loss of a friend who died years ago of AIDS. An Awesome Gap helped me accept my son’s devotion to skateboarding—and therefore who he is as a person—even though I didn’t fully understand it. Each time I succeed at imagining a story, I think I evolve a bit as a person. It’s hard to explain, because these stories aren’t about specific things I’ve gone through. And yet, they each do the job of helping me to move forward in life with greater understanding. Perhaps they do something similar for the reader. To me, at least, this explains the joy I feel when writing each and every one of them.

Describe your process. How do you go from idea to first draft, and first draft to final draft?

These stories come out of small gems of understanding and serendipitous moments when life suggest deeper meanings. One Easter morning, at a brunch in our backyard, my husband and I realized that our young son had dug up a dead bird he and his father had buried a few days before. We were suddenly dealing with a resurrection on Easter morning—almost too perfect a gift—and I had to use it as inspiration for a story.

After considering some specific conundrum or irony of life, I write a draft, then rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, sending out the story to literary magazines and getting it back, then revising more until it’s finally placed. It’s a long process. The stories in Shelf Life of Happiness were written over a dozen years and rewritten all along the way. I even continued to edit on the spot during a recent reading.

You’ve also written two award-winning novels: Dreams of the Red Phoenix and River of Dust. How do story-writing and novel-writing differ for you?

A story can come from a single idea or gem of understanding, but a novel has to have many themes and characters and an arc that can sustain it. A story is more of a snapshot, although I like my stories to have a beginning, middle, and end. By the end of a story, I want my reader to have a feeling of completion. Each one should be a small sculpture—coherent in theme and style and execution. In a novel, there’s more room for elaboration and excess. I like my stories to be tight.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on something very different. A Woman of Letters is a novel set in 1890s Boston, about a woman who writes romance and adventure tales and must fight to be taken seriously in the world of men of letters. She decides to change her writing style to be more literary, upending everything for herself and her publisher, and ultimately allowing romance to leave the page and enter her life. It’s a feminist tale, and a writer’s tale, and a lot of fun!

Shelf Life of Happiness Explores Complexities of Love

Ellen Birkett | February 1, 2019

Virginia Pye had always written, but when she took a class from Annie Dillard at Wesleyan University in Connecticut she began to get a deeper sense of what writing requires. “We worked on one story for a single semester. I learned then that writing is rewriting and it is important to be tough with yourself,” said Pye.

I learned then that writing is rewriting…

That practice of writing and rewriting, sending stories to literary journals and revising them when they came back, led to the development of her short story collection, Shelf Life of Happiness. The stories in the collection, some of which appeared in The Baltimore Review, Tampa Review and Prime Number Magazine, deal with regular people as they try to navigate the complexities of relationships and the challenges of communication. “Chekhov wrote about everyday people in regular circumstances, where all their foibles, confusion and mistakes were revealed. His characters bungled things up, but he didn’t look down on them. People trying to do their best; those are my people,” said Pye.

-

Her stories were written over the course of twelve years and several were finalists in writing competitions. During that time, Pye authored two novels, Dreams of the Red Phoenix and River of Dust. “My short stories cover a smaller canvas, a shorter period of time. They deal with a singular revelation or series of revelations,” said Pye. Her novels, both set in China, deal with broader themes and often start with the exploration of a setting or landscape, which she populates with characters.

The inspiration for Pye’s short stories “tends to come from little moments, little gems, that offer insight into life and character. They come from key moments where something crystallizes the meaning of life.”

One such incident, when on Easter morning she found her son had dug up a dead bird that had been buried in the backyard, became the inspiration for her story Easter Morning, with its themes of death and resurrection.

Art comes from trying to understand how others see things.

The title, Shelf Life of Happiness, comes from the focus on the characters’ striving and longing for happiness, however fleeting it might be. Pye relishes the opportunity to explore the ambiguity that comes with human communication. “Art comes from trying to understand how others see things. Perspective is like a prism, there are lots of ways to see things,” said Pye.

She works to make sure the endings of her stories give the reader a sense of what is happening and where the story stands.

The greatest challenge when developing the collection was the “continuous revising” as she worked on the stories over the years. “The challenge is to keep trying to figure out what the stories are about and to stay interested enough in them to make them better.”

The collection found a home with Press 53, where it was a finalist twice in their annual contest. Editor Kevin Morgan Watson helped Pye shape the collection into a cohesive whole in terms of themes and point of view (third person).

Pye urges apprentice writers to take their time and not share their work with peers until they find their voice and feel confident. “Do develop peer relationships, go to readings, and go where writers are. But get a few drafts in and have a sense of what your work is so that you know what to make of feedback when you get it.”

She is currently working on a historical novel, set in the 1890s, about a woman writer seeking parity.

Inside the Writer’s Studio

An Interview with Virginia Pye

Charlie Lovett | November 29, 2018

Charlie talks with award-winning author Virginia Pye about her newest collection of short stories Shelf Life of Happiness. They delve into the nature of short stories and of storytelling, inhabiting characters across differences, setting as character, and even how the weather can effect the mood of a story. If you've ever tried to write a short story, you’ll want to listen in! LISTEN HERE

Work-in-progress

Virginia Pye, Shelf Life of Happiness

Leslie Pietrzyk | November 28, 2018

Give us your elevator pitch: What’s your book about in two to three sentences?

My characters long for that most elusive of states: happiness. One reviewer called these stories bittersweet, and I agree they combine heartbreak and joy in equal measure. A young skateboarder reaches across an awesome gap, both physical and emotional, to reconnect with his disapproving father. An elderly painter executes one final, violent gesture to memorialize his work. A newly married writer battles the urge to implode his happy marriage. And a confused young man desires his best friend’s bride and, in failing to have her, finally learns to love. In each story, my characters aim to be better people—and some even reap the sweet reward of happiness.

Which character did you most enjoy creating? Why? And, which character gave you the most trouble, and why?

I most enjoyed writing the old artist character, William Dunster, in the story White Dog, because he’s cantankerous and befuddled and more than a little bit drunk, yet also wise. He observes the other characters and the manicured setting in the Connecticut countryside with an air of detachment, seeing through the gallery owner’s vanity and his wife’s unhappiness. Basically, Dunster can’t turn off his bullshit detector, so he’s thinking what we all might be thinking if we allowed ourselves. Plus he’s especially smart about art. What matters most to him is “the ongoing lover’s quarrel with the work.” A part of me feels that way, too.

-

Tell us a bit about the highs and lows of your book’s road to publication.

This book has a lot of good karma behind it, or maybe a better word is kismet. It was runner up for the Press 53 short story collection prize twice and Kevin Watson, the publisher and editor, wrote to me soon after the second time to say they should publish the collection. But for some reason I never got that email. About six months later, I wrote to him to suggest the same thing. And later, I was delighted to have one of my closest friends create the beautiful cover. We’ve also gotten the most moving responses from writers who I admire enormously. The whole thing feels like a happy labor of love.

What’s your favorite piece of writing advice?

Write. That’s about it. Just sit down and do it. The process will teach you things that no one and nothing else can. Trust that you’ll improve with practice. Assume you’ll write many things, so don’t get too attached to one. But mostly, just write.

My favorite writing advice is “write until something surprises you.” What surprised you in the writing of this book?

I wrote these stories over a ten-year span, and while I sensed they had something in common, it wasn’t until I started to pull them into a collection that I discovered the theme of happiness—or the theme of the search for happiness. I realized that each story, in its own way, was about that striving, that universal longing.

How did you find the title of your book?

Strangely enough, the title was originally from a story that didn’t make it into this collection. I had written a short short set in a grocery store, where a woman is on the phone with her brother, who is at the hospital with their dying mother. The woman wants to escape the sadness of losing her mother by noticing simple things like the brightly lit fruit, but instead, all she can see is how everything is tainted with sorrow and decay. She thinks about the literal shelf life of grocery items, and the phrase shelf life of happiness crosses her mind.

Fast forward to when I put together this collection and I realized that story, while one of my favorites, didn’t fit because it was told in the first person and all the others were longer stories in third person. But I realized that the idea of a shelf life of happiness fit with many of the stories. It struck me that an altogether different character named Gloria Broadhurst, who is a bit of a grand dame, might actually say that phrase aloud, because she’s clever and wrestles unabashedly with her own unhappiness. Gloria would feel comfortable making a pronouncement using that phrase. So I plugged it into that story and then changed the title of that story to Shelf Life of Happiness.

This helps to illustrate my earlier writing advice: assume you’ll write a lot and it’s all yours to mess with, tear apart and build back up, ruin and perfect, and enjoy!

Inquiring foodies and hungry book clubs want to know: Any food/s associated with your book?

You’ve stumped me on this one. I never noticed that my stories are so lacking in food! Off the page, I love Italian dishes (and was just there again this summer and had some amazing meals), and Moroccan, and French, and Indian; you name it, I like it! But in my stories, my characters clearly need to eat more.

I see that only one character has a food recollection: the mother in Her Mother’s Garden shares a distant memory of a meal she had on a cliff-side restaurant in Greece. She’s never mentioned it to her daughter before, which only makes the daughter feel more desperate about holding onto her mother before it’s too late. So food, in this case, shows how private pleasures are often kept hidden, even from those we love, and how the longing for happiness and connection can attach itself to even the most pleasant of reflections.

Christi Craig

Q&A with Virginia Pye,

Author of Shelf Life of Happiness

Christi Craig | October 24, 2018

“Some people seem willing to do anything to be happy, even if it means becoming colossally dull,” Gloria continued. “But everyone knows it’s fleeting. There’s always a shelf life of happiness.” [From Shelf Life of Happiness]

Being happy should be easy. We have plenty of resources around us that make it so: podcasts set on discovering it and books built around cultivating it, just to name a few. Yet Happiness is fleeting. While other authors are writing about reclaiming it, maintaining it, and preserving it, Virginia Pye has written short stories that define it in simple terms and give us a view into our own humanity, how we tend to overlook it, exploit it, or misinterpret it.

In her new book, Shelf Life of Happiness (just out from Press 53), Pye fills the pages with unexpected sensations of affection, of freedom in truth, of realizations about what it means to be happy–or in love–but sometimes a little too late. Jim Shephard calls these “deft and moving stories.” Kelly Luce says these are “stories crafted with a sharp eye for the absurd intricacies of modern life…remembered later with such clarity and feeling that they seem like one’s own memories.” I call them tiny revelations packed in 169 pages. (Sure it could be 170, but would that really make you happier?)

-

I’m honored to host Virginia Pye to talk more about her book and her writing. Welcome Virginia Pye!

While Shelf Life of Happiness isn’t your first book, this is your first collection of stories after two successful novels (River of Dust and Dreams of the Red Phoenix). Considering how you’ve taken a path opposite of many authors, who begin with a collection and journey to longer works, what has been the most rewarding or compelling aspect of writing and publishing this new book?

I’ve written stories from the start, way back to high school or earlier. Like a lot of beginning writers, I tried to channel Hemingway and Faulkner, Calvino and Carver. But the nine stories in Shelf Life of Happinesswere written over ten years more recently. I wrote them from an impulse to explore a particular moment or thought. Some irony of life, or question, strikes me and I need to flesh it out. Writing my novels is much more involved and immersive, but the stories can be every bit as exacting. I rewrite them over months and years as I send them out to literary magazines. When a story is returned, I often revise it before sending it out again.

I loved pulling together this collection, because it showed me that I’ve been chewing on some of the same themes for years—the illusive nature of happiness, the bittersweet nature of love, the struggle to ever know another person fully. And also, how a dedication to art—which to me means writing as well as visual art—can help guide a life and make sense of it. Some of the stories in Shelf Life of Happiness are about writing itself—the redemptive human effort to find order and beauty.

One of my favorite quotes from your book is in the story, “White Dog:”

[Dunster] struggled to understand why he’d pulled the trigger. Rob Singh had wanted to preserve his impeccable vista, but didn’t he know that perfection smelled like death? With that one shot, Dunster had upped the ante and shown Rob that he was wrong not to make his peace with the smudge on the horizon, the mistake on the canvas.

So much of your collection is about accepting life’s imperfections and coming to peace, and you tell your stories from the perspectives of a variety of characters: an elderly artist, a young skateboarder, a mother on the verge of breakdown. Where do your ideas for characters–their strengths and their flaws–come from?

Like many writers, I transpose my life and everything I’ve ever read into fiction, though how exactly, or why, isn’t clear to me. It helps to be a bit older and to have had years to work things out. These days I keep remembering things my father told me near the end of his life that turn out to be wise in a pragmatic way. I didn’t realize at the time that what he was offering was valuable, but I see it now. My characters seem to come out of an accumulation of understanding.

But, to be more specific, the stories in Shelf Life of Happiness are about people I could know, and maybe the reader could know, as well. I cull details especially from those I love. The skateboarder in my story, An Awesome Gap, is definitely not my son, but my son does happen to be a skateboarder. I’ve seen his dedication to his “art,” though he’d never use such a glorified term for skating day in and day out in all kinds of weather. Also, I think we all know how even a good kid has to struggle to break free from his or her parents’ expectations. The teenage character in that story deals with that issue, too.

I’ve known artists like Dunster from White Dog, but that particular character is more than an amalgam of all the male artists I’ve ever sat next to at art museum dinner parties (my husband is a long-time curator and art museum director). Combine those experiences with everything I’ve ever read about artists, plus what I’ve learned myself about sustaining an artistic life, and you have Dunster. Though I suppose that doesn’t fully explain where my characters come from, either.

In your essay, “A Zealot and a Poet”(on the Rumpus), you write–so beautifully–about discovering your grandfather’s journals that detail his experiences as a Congregational missionary in China during the early 1900s, and the surprise in finding he was much more than a missionary. He was a writer. In fact, he became the inspiration for the protagonist in your first book, River of Dust. How does his writing, his presence in your writing, continue to influence your work?

Thanks so much for reading that essay. I’m proud of that one and appreciate you tracking it down. I don’t think my grandfather influences me much any longer, though his actual words and their cadence did help me create the voice for my debut novel, River of Dust.

But, since I mentioned my father earlier and now you offer this question about my grandfather, I wonder if you might be onto something: perhaps there is some way that I’m writing to keep up with them. They both believed their voices deserved to be heard. That sense of confidence may have come from white, male privilege, or a misplaced entitlement. But they, and my mother, were great readers and books crowded just about every surface in our home. My father wrote his many books and articles in long hand on yellow pads in the midst of our family activity, sometimes with the Celtics or Red Sox on the TV. Writing was something “we” did. I’m grateful to him and my mother, and even my grandfather, for that.

Though, to share more, it took some determination on my part to claim writing for myself. I remember distinctly that my father didn’t think I was a good writer when I was teenager—he thought of me as scattered in my thinking, which I was, and considered me more of a “people person” than a writer. As a girl and a youngest child, I’d been trained to be helpful and accommodating, not assertive with ideas and words. To convince my parents to help pay for grad school, I told them I needed an MFA to teach writing. They could see me as a teacher, but not as a writer. I remember reassuring them I wasn’t trying to win the Pulitzer Prize. That seemed to set them at ease. I think they didn’t want me to deal with the disappointment that writers inevitably face. But also, they didn’t think I could do it because I was a girl.

What are you reading these days?

I read several books at once, all novels or short stories. Some are for research for my next novel, which is set in 1890s Boston. Katherine Howe’s historical novel from several years ago, The House of Velvet and Glass, is entertaining and smart. But right now I also have Laura van den Berg’s The Third Hotel and Susan Henderson’s The Flicker of Old Dreams on my bedside table. As always, there’s too much to read!

What is your favorite season in which to write?

When my children were young and we went on vacation to Maine in the summer, I’d get up early in the mornings to write. It was so peaceful and rewarding because I knew the rest of the day would be packed with family outings. I loved the quiet as the birds started to stir and the sun rose over the ocean, followed all too quickly by the cacophony of young voices and little feet pounding on floorboards.

But these days, as an empty nester, I have lots of time and tend to buckle down in the colder months, when there are fewer distractions. Boston turns out to be a great book town, not just because of the wonderful bookstores, or because of GrubStreet, the writing organization, but because the weather is so lousy so much of the year. You simply have to stay indoors and write!

I feel lucky to join the throngs of writers, both past and present, who have made this city their home. As we head into winter, when mornings start out cold and dusk comes early, I look forward to hunkering down at my desk.

Book Q&As with Deborah Kalb

Q&A with Virginia Pye

Deborah Kalb | October 23, 2018

Virginia Pye is the author of the new story collection Shelf Life of Happiness. She also has written the novels Dreams of the Red Phoenixand River of Dust, and her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The North American Review and The Baltimore Review. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

How long did it take you to write the stories in this collection, and how did you decide on the order in which they’d appear?

I wrote these stories over many years, with the earliest published a decade ago. All are told in third person, inviting the reader into the thoughts and feelings of disparate characters in widely varied settings.

Most important to me when deciding the order was trying to assess how the stories might make the reader feel. Each story has its own internal arc in terms of plot and emotional resonance, and the collection overall builds in momentum as well, in a similar way to how a novel unfolds.

-

Do you see any themes linking the stories?

The elusive nature of happiness is the overarching theme and it’s woven throughout each of the stories, though how it’s revealed differs a lot depending on the main character.

A young art dealer tempts a grizzled old artist to reshape himself in order to have a final chapter of his career; a son reaches for his father across a widening gap to convince him of his passion for skateboarding; a wife and mother in the Roman ruins is lured away from her family by the suggestion of forbidden love: each character must navigate easy temptations as they search for true fulfillment.

I like the way Jim Shepard describes the lives of my characters “as a tangle they urgently need to understand before it’s too late.”

He goes on to say, “They’re experts on how to keep their hearts in reserve, and they recognize the ache of their own shame in their fear that perhaps those lesser versions of themselves they so often glimpse are who they really are, and yet all they want is to access the appreciative tenderness that’s waiting for them within their best selves.”

My characters try hard to be decent and when they ultimately succeed, a certain happiness is their reward.

How was the book’s title (also the title of one of the stories) chosen, and what does it signify for you?

One of my characters, Gloria Broadhurst, an elusive, far from happy figure, utters the phrase “shelf life of happiness.” She asks, “When it comes down to it, who is happy these days, that’s what I want to know? Really. Tell me. Who is?”

Her old friend, a husband and writer who’s been in love with Gloria for years, puts his arm over her shoulder and knows the answer for himself, but doesn’t dare say it aloud, “for fear it might disappear on a cloud of moist breath and air.”

He doesn’t want to take his happiness for granted or jinx it in any way—that’s how precarious and precious it is. If we’re lucky enough to be happy, as I can say I am in my life, we must also know that life is full of grave uncertainties and nothing guarantees we’ll stay happy. My characters wrestle with this urgent understanding.

Have you read any short stories lately that you particularly admire?

The final collection from the Irish writer William Trevor is unbelievably beautiful, his language precise and his touch deft. I sometimes have to read his stories several times over because his character’s inner lives are shaded with such subtlety.

And I can’t resist mentioning the extraordinary stories of Jim Shepard, whose imagination is more elastic than just about any other writer today. I have no idea how he puts himself into the minds of Neolithic characters, early French aeronauts, or pioneer wives of the 1800s. Yet somehow his stories feel current, not fussy or old. He’s a ventriloquist and a magician of sorts.

What are you working on now?

I’m returning to the literary/historical territory of my first two novels, though this new book isn’t set in China. It’s a story about a woman author of dime novels in snobbish, literary Boston and Cambridge of the 1890s.

It’s a feminist tale based on a real character, and also a story about writing, creativity, the publishing business, and Gilded Age New England. I grew up in the Boston area and recently returned after 35 years away, so I’m approaching my subject with a combination of fresh eyes and a deep love of home.

Anything else we should know?

People may think that reading fiction is frivolous in a time of great uncertainty, but literature invites us to keep our minds open and our hearts compassionate. We need that now more than ever.

Read Her Like An Open Book

Book Chat: Virginia Pye Talks About Her New Book, Shelf Life of Happiness

Margaret Grant | October 22, 2018

I met Virginia Pye through the Association of Writers & Writing Programs’ (AWP) Writer-to-Writer Mentorship Program. Virginia chose me to be her mentee for three months last year, a relationship that has grown into a friendship. I jumped at the chance to speak with Virginia about Shelf Life of Happiness, a collection of stories with characters that really got under my skin.

These stories are quite different from your novels. I’m so impressed by that range. In what ways do you find writing short stories different from writing a novel? How do you shift focus, and do you struggle with that?

I’ve written short stories off and on for thirty years, but I don’t have a large number of them to show for it because I only write them when a gem of an idea comes to me. Something strikes me as ironic or problematic or a small crystallization of life’s conundrums. I have to work it out in a story. For me, writing stories is like writing poetry in that way—it’s about scratching an itch.

-

Novel writing is an altogether different process. It requires advance planning, often research, and major organization of ideas. I’ve sometimes used note cards to plot out the shape and I write in scenes from beginning to end, constructing the narrative arc as I go. I tend to do my character building within the confines of the story I create—probably because my novels have a lot of action. The plot—what happens to propel the story forward—reveals my characters. Maybe if my novels were more internal, like my short stories, I might construct them differently.

What shines in the whole collection is the complexity of your characters. This requires such deep diving into the emotional ocean that so many of us try to avoid. What is your process for character development, by which I mean, do they arise fully formed, or do you go over and over the work to bring them to life? What is the hardest thing for you personally to go through in creating such vivid characters?

I revise many, many times, and often over many months or even years. I send stories out to literary journals and revise when they’re not accepted, so the process is an extended one.

The hardest thing, I suppose, is how to limit what readers learn about each character, pinpointing the most essential information or impression. A short story, needless to say, has to be short, so a writer needs to be discerning. The process requires a lot of building up and then winnowing down. I think I’m more naturally a novel-writer, so it can be painful to pare down to the essentials in a short story.

I loved “Crying in Italian” and was surprised and relieved by the ending. It was handled so delicately. What does the ending mean to you? Is it too late for them, do you think?

I leave it to the reader to decide if the wife and mother in this story will be swept away by the passion she senses all around her in the Roman ruins, or literally stay on the “right” path with her family. This is one of the few stories I’ve written with a more ambiguous ending, though I think the main character’s direction is pretty clear. In general, my work is less ambiguous than a lot of contemporary literary fiction, in which actions are taken without consequences and relationships have hazy reasons for being or dissolving.

I think some people consider ambiguity in fiction to be more sophisticated than certainty. But my characters’ whole reason for being is to face those moments in which they must step up to the plate. For example, in my novel Dreams of the Red Phoenix, the story hinges on whether the mother will set aside her personal ideals and protect herself and her child in the midst of war. In River of Dust, the stakes are every bit as high, and the characters either crumble or respond nobly. It’s an old-fashioned idea, I suppose, that fiction is an appropriate venue for the exploration of morality, but that’s my quiet goal.

Many of the stories prompted me to say out loud, “No, don’t listen to him!” as in “Her Mother’s Garden.” This is a story about class divisions, how society responds to that, and how such divisions have changed over time. Can you talk a little bit about where this story came from?

As my parents aged and my father was diagnosed with incipient Parkinson’s, they had to move out of the home where I grew up. Surprisingly, someone I’d known growing up bought the house and tore it down. At the time, and for years afterwards, I felt pretty shocked and hurt by that turn of events, especially because it was at the start of a period of great loss—first with my father dying and then my mother. Part of my process of grieving was about the destruction of the house as well.

But with time, I came to realize that the house being material—still standing, that is—didn’t matter. The memories I have of it are so removed from the present, it wasn’t important that the actual structure existed or not, in much the same way I now realize that my parents, though gone for a decade, are still with me.

So, that story came out of grief, but also out of a deeper understanding of permanence in life. How what you love and whom you love are always with you.

And yes, it’s also a story about class—how the old money ways of the past have been superseded by new money and different values. But I think, or hope, that the story also suggests that those new values have merit, too. The man who buys and then tears down the home in my story is a real family man. He’s looking out for what’s best in his eyes for his family. He’s not a bad guy, in my opinion. And the end result, as in so many of my stories, is that the main female character is forced to see the world differently. She must leave the bubble of the protected, precious world her parents created. I hope the reader senses that she will be the better for that change, although it’s not an easy one.

In the story “Redbone,” the main character is a rather loathsome individual. And we get different perspectives, including his own, throughout the story. We have plenty of reasons not to like the guy, and yet I still was hoping for the best for him right up to the end, which I think is a sign of a very well-crafted character and story.

Redbone put ambition above all else—and not a healthy type of ambition, but ambition of the sort that caused him to lose those he loved. He’s literally and figuratively lost his bearings in life and in the ocean where he swims. So, I think he’s getting his just desserts, but I hope the reader also feels for the man. He wanted to be a better person, and in the end that’s all we can hope for—to have that impulse to be decent and kind to one another, even if we can’t pull it off all the time. I see myself in him—me at my most crass and grasping—and I hope the reader can see him or herself, too. It’s a bit of a cautionary tale, but one I need to remind of myself, too.

The inevitable question arises — what are you working on now?

I’m excited to be working on an historical novel set in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I grew up and now live again, but not set in the present, instead in the late 1800s. It’s the story of a woman author of dime novels in the world of high literature. I’m having fun with feminist themes in a Gilded Era setting. I love thinking about highbrow, snobbish Boston as immigrants changed the character of the town. It’s so clear how the same societal issues were at play then as now, as well as in my novels and in the stories of Shelf Life of Happiness.

Fiction Writers Review

An Interview with Virginia Pye

Janyce Stefan-Cole | October 22, 2018

Virginia Pye is the author of two novels, Dreams of the Red Phoenix (Unbridled Books, 2015) and River of Dust (Unbridled Books, 2013). Both take place in China and involve historical events; both evolved from her grandparents’ experiences as missionaries and her father’s having been born and raised in China. She now has a collection of stories, Shelf Life of Happiness, due out from Press 53 this October.

I’m in awe of any writer who can pull off both novel and short story. I was told in workshop years ago that I’d write novels. I was afraid of such ambition as I submitted story after problematic story to the group. Virginia Pye’s stories are concisely drawn with an enviable array of diverse characters. Her plots operate on an emotional plane: a slight shift in perspective, an abrupt act, an unexpected response move the stories forward. There are no grand gestures, only the circumstances of a life. William Trevor described the short story as “the art of the glimpse.” What a feat to go from the long gaze of the novel to that intimate glance.

With an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, Pye has taught writing at New York University and the University of Pennsylvania. Her essays and stories have appeared in the North American Review, The Baltimore Review, The Rumpus, Literary Hub, Huffington Post and The New York Times. Noteworthy too—Virginia Pye kept her cool when she ran into Mick Jagger at a Shanghai bar.

-

INTERVIEW:

Reading your stories I feel as if I’m peering into your characters’ lives through a window, almost inappropriately compelled to keep watching. Yet these quintessentially American stories are packed full of familiar places and situations any of us might encounter. You are wonderfully observant. How did you find these stories?

Without trying to sound too mystical, I feel that these stories found me. If I notice something that’s quirky or unresolved—a little gem of experience that captures life’s ironies or conundrums—I start to imagine resolving it in a story. Though, of course, fiction never resolves anything. Instead, it opens more avenues of thought about life, rather than narrowing them down. But still, I use fiction to explore small moments that have leapt out at me as rich with possibilities.

You have said, “Fiction gains its full scope when an author takes a daring imaginative leap fueled by empathy and understanding.” Orhan Pamuk speaks of the writer’s compassion for his characters. Yet there’s an argument afoot that a writer ought to stick within his or her—especially ethnic—experience. Well, first off, that would preclude murders from most fiction, or a female writer creating a male protagonist, or possibly, too, books written about a foreign country in a different era. To me your quote perfectly states the writer’s gift: imagination and empathy. (Which does not imply either is easy to exercise.) Can you comment?

Fiction relies on the suspension of disbelief, and to achieve that is not as easy as it sounds. To get a story or character right, you have to really know your subject, which doesn’t mean knowing every detail, just the right details. The essence.

I agree with the perspective that writers from dominant cultures must bring an especially sensitive and self-aware approach to telling the stories of people who have had vastly different life experiences from the author’s own, and who have perhaps faced oppression that the writer’s own group may be responsible for. That’s what I tried to do in my two novels. When a writer does choose to portray someone from an oppressed group, she needs to be aware of the bias with which she approaches her story. Compassion and empathy and respect must be the guide.

There’s a passivity running through many of your characters. In “Her Mother’s Garden,” Annie is ever stunted as the garden thrives. This is an interesting take on mother and garden as metaphor: nourishing forces become almost like kudzu, invading and choking the spirit. A similar passivity engulfs Sara in “Crying in Italian.” She seems ready to suffocate with unhappiness but, unable to confront it, she wanders off from her children to watch a couple making love among the Roman ruins. In “New Year’s Day,” Jessica horrifically speaks her mind to the last person to connect with a murder victim, behavior that disrupts Jessica’s sense of who she is.

I find truthfulness in these characters’ passivity, their indistinct dissatisfactions. Tell me about that, where these characters come from. How do you know them so well?

Actually, this question follows nicely on the one before it, because I think that passivity I explore through my characters comes out of a feeling of separateness and disconnection from the world. My characters often feel they aren’t a part of the mix. They’re not rubbing elbows with others who are unlike themselves. They’re on the outside. This could be because of being raised in the suburbs; I’m the child of intellectuals; I was the youngest in my family by many years and felt like an only child; and I’m a writer—whatever the cause, the point is, I can relate to feeling not connected enough.

My characters—especially in my novels—often make foolish choices to break free from that feeling of being removed from life. Sara, in the story you mention in the Roman ruins, is literally heading off the path in order to find more passion and more life-giving feeling. My characters create conflict, they take journeys, they convince themselves they are finally prepared for what the world has to offer them—in other words, they plunge in, for better or worse.

The stories “Redbone” and “White Dog” involve older male artists who have or will achieve a measure of success that conflicts with every other part of their lives. Artists sacrifice for their work, and the personal—especially the family—often suffers. There is the suggestion, too, of a time when artists were viewed as larger than life—dedicated, forceful but flawed—and that that may no longer be so.

Do you believe the artist is a diminished force in society today, possibly because of the sacrifices involved in what could be called, without pointing fingers, anti-heroic times?

Actually, I think the artist today is as important, perhaps more important, than ever. Artists have always taken up the mantle of social activism and do so crucially at this time.

I think the two male artists who you mention are actually admirable, though cranky and narcissistic, especially the older one in “White Dog.” He has a philosophy about his work that I try to aspire to. At one point in the story he says that what matters in life is “the lover’s quarrel with the work.” He has dedicated his life to getting it right. He believes in the dab of paint on the canvas, the necessary imperfections required by art, instead of the sanitized version of things that so many non-artists (like the gallery owner in the story) try to pursue. He wants life with all the messy parts, and yet, ironically, he strives for it by staying in his studio year in and year out. To me, that’s pretty heroic.

Nathan, in “Shelf Life of Happiness,” is relieved he won’t have to become lovers with the beautiful, connected Gloria. It takes a stranger from the Ukraine to unstick an awkward moment, in “Easter Morning,” of a young boy harboring a dead bird. Keith, in “Best Man,” literally needs direction from the dead.

Some of your characters seem adrift in their fates. Would you say you had a sympathetic yet pessimistic view of those lives?

I think that by the end of each of those stories, despite whatever ways the main characters have felt limited in their lives or lacking in courage, they rise to meet the challenges set before them. They shrug off their own weaknesses and become better people. At least that’s how I intended them to be seen. I am sympathetic to them and maybe even optimistic. They’re weak, but they strive to be strong. That’s pretty much all we can hope, I think.

An exception is the twelve-year-old skateboarder, Patrick, in “An Awesome Gap,” who shows resolve and grit: “No one in his family got it that you had to live in the moment and do what you love to do.” His father works hard to “pay for stupid stuff.” There’s a terrific tension between this unfiltered boy and his father—the growing gap not just between father and son, but between raw power and compromise. I’m thinking of Freud’s Society and Its Discontents: the effort to reach our full potential while trying not to be twisted in the kudzu of constant compromise. Is it correct to suggest your stories reflect a sense of struggle for self-realization?

I think that’s a good way of putting it. The boy in this story, like the older artists, has a mission he’s trying to accomplish. He wants something very badly—to be a good skateboarder, even a great one. That striving makes him an artist. I admire that in people. How, whatever your field, you might have in your mind a higher level of accomplishment or self-definition you’re trying to achieve. Ambition can be seen as bad, or selfish, but if it comes with a greater self-understanding, then it’s good. So, yes, my characters, like so many characters all the way back to Ulysses, struggle to achieve their better selves.

Finally, you have a book coming out! Always a nervous thrill, the realization of a book, a need met, your words and thoughts will be read. Which satisfies Virginia Pye most, writing a book or seeing it realized? Both, of course, but I ask this because the challenges of publishing are so much greater now, and I think the writer inevitably confronts the question: Would I continue to write without being published—assuming self-publication for one reason or other is not an option?

For the longest time, I wrote without being published, so I know all about that. I had my first literary agent when I was twenty-seven but my “debut” novel, which was really my fifth written, was published when I was fifty-three. I can write without a guarantee of being published and it’s important that all writers can, especially, as you say, in this fickle, difficult market.

But I’m very happy and satisfied when a book does finally come out. The stories in Shelf Life of Happiness were written and published in literary magazines over a full decade. They capture how I’ve thought and what I’ve cared about for years. To finally get to share them is a gift to me, and, I hope, to the reader as well.

Dead Darlings

An Interview with Virginia Pye,

Author of Shelf Life of Happiness

Jodi Paloni | October 16, 2018

We at Dead Darlings are thrilled to share author Jodi Paloni’s interview with Virginia Pye about her forthcoming short story collection, Shelf Life of Happiness, which Kirkus Reviews called “…a deeply moving meditation on the complexity and potential generosity of love.”

Virginia is also the author of two award-winning novels, Dreams of the Red Phoenix and River of Dust. Her stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in The North American Review, The Baltimore Review, Literary Hub, The New York Times, The Rumpus, Huffington Post and elsewhere.We hope you can join Virginia for the book launch for Shelf Life of Happiness at Porter Square Books on Tuesday October 23, 2018 at 7:00 pm.

Virginia, I’m so excited about Shelf Life of Happiness. I got into bed early on the longest day of the year planning to read a story or two, and before I knew it, I finished the book. It was some time in the middle of the night, my husband snoring heavily beside me, that I was struck by the breadth and depth, the range of motion, in your collection—time and place, seasons and weather, character and tone and point of view, relevant content—while at the same time, I felt as though a steady beat was being struck throughout. After I thought about it some more, here’s where I landed: While reading about the tumultuous and often disturbing lives of your characters, I actually felt quite grounded. I think it has to do with how you deal with place as a mirror, the great pause in the fever pitch of a character’s trajectory, and also, how compassionate you are towards your characters. But more on that later. Let’s begin with place.

-