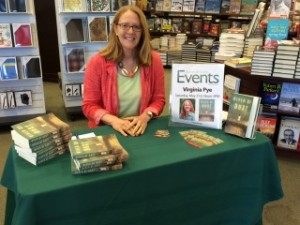

On a recent sunny Saturday in May, I sat at a table just inside the door of a Barnes & Noble in my hometown and hawked my wares. I’d done book events at the two indie bookstores in Richmond, and was now happy to be hosted by the community relations manager at the B&N nearest me—a friendly, tattooed man who’d recently moved to Richmond from Brooklyn, where he’d also sold books. I was touched when he said he’d read my novel and thought it was excellent. Booksellers have so many books to read, and I was honored that he’d taken the time to read mine. He seemed excited to have me at his store, and I overheard him telling shoppers and other B&N booksellers that he loved my novel and they would, too. In other words, he wasn’t just a nice guy, he was doing his job. As I sat at the table they’d set up for me, I quickly realized that I must now do mine, too.

On a recent sunny Saturday in May, I sat at a table just inside the door of a Barnes & Noble in my hometown and hawked my wares. I’d done book events at the two indie bookstores in Richmond, and was now happy to be hosted by the community relations manager at the B&N nearest me—a friendly, tattooed man who’d recently moved to Richmond from Brooklyn, where he’d also sold books. I was touched when he said he’d read my novel and thought it was excellent. Booksellers have so many books to read, and I was honored that he’d taken the time to read mine. He seemed excited to have me at his store, and I overheard him telling shoppers and other B&N booksellers that he loved my novel and they would, too. In other words, he wasn’t just a nice guy, he was doing his job. As I sat at the table they’d set up for me, I quickly realized that I must now do mine, too.

Being a writer today requires a skill set beyond what’s needed to create a book. As it turns out, you also need to be able to sit attentively for hours in public and smile in a welcoming, inviting way at strangers. I don’t believe that at any moment I actually leered at people, though I did occasionally catch myself leaning too far over the table as shoppers entered the store, hoping, unconsciously, to draw them magnetically towards me and the stacks of my novel, River of Dust, displayed on the table.

If a shopper came within, say, three feet of the table and so much as snuck a peek at my book, I launched into a description—gauging the intensity of my pitch according to whether they stood their ground, inched closer, or backed away. Body language is remarkably clear: when someone’s not interested, they simply leave.

Not many folks did that, though, because they were basically polite and decent, and once I started to talk to them they tended to move closer. They seemed to feel at least as awkward as I did about the whole business. They began to touch things on the table: my stacks of books, the bookmarks I had arranged in a pretty fan, my little pile of business cards, searching, I sensed, for a way to anchor themselves.

Perhaps this is a good moment to mention that a fascinating cross section of America walks through the doors of a Barnes & Noble on a sunny Saturday afternoon in May. Friendly people, most of them, but also some fascinating bookish types who appeared to have gone there on intensely bookish missions. Others hovered through the store, their fingers grazing the book covers, but never picking one up. As odd as some people seemed, I felt predisposed to like them all since they were ostensibly readers and on a beautiful spring day they had chosen to visit a bookstore.

When a customer did finally stand before me, I beamed up at him or her (more often her), and began: the book is set in China in 1910, the story of an American missionary couple whose toddler child is kidnapped, lots of adventure, opium dens, but also about faith and belief, different world views, differences between East and West, deep and yet fun, serious and yet something else, a lot else—and with each sentence and phrase, I felt my novel decomposing in my hands like a wad of pulp in the rain. What I really wanted to say to them was that the only way to know what it’s about is to read it.

But instead, as I spoke, I assessed their moment-by-moment level of interest: if the mention of something exotic like an opium den seemed to catch their attention, I’d throw in hints of a traveling circus or a beheading, or an aside about Rudyard Kipling and Colonial literature. If they seemed more engaged by issues of spirituality and faith, I described my characters’ wavering devotion; if the cultural differences between East and West sparked their interest, I’d embroider with some improvised riffs about the U.S. and China today.

As I spoke, I realized this is how people sell things, any things, all things. This is what we do in our country: we size one another up, figure out what the other wants, and then do our best to offer it. That may seem incredibly obvious, but that thought, that very concept, had not previously been in my repertoire as a writer. Some writers write what they think the market “wants,” but I’ve never deliberately done that. I suppose we’re all influenced by the commercial tides around us and create accordingly, but that’s never been my conscious intention.

But now, I was a salesperson for the imagined world I had created in my novel. And although I was new at this, it turns out I sold a good number of books that day and had a good time doing so. I liked talking to strangers. They were smart and funny and respectful and told me what books they had enjoyed reading recently and what they didn’t like in a novel.

When I mentioned the kidnapping at the start of my story, one woman threw up her hands and said it sounded too terrifying and real for her to read. No matter that my kidnappers were Mongolian bandits on the northwestern plains of China in 1910. Another woman, after I’d gone on a little too long describing my story, quietly explained that she only read SciFi and Fantasy.

Then there were some readers who interrupted my sales pitch mid-course to say mine was exactly the kind of book they loved and they wanted to buy several copies. I was just as curious to ask these readers how they knew they loved it as I had been to ask the SciFi/Fantasy woman why she never read anything else.

An old adage started to come to mind: there’s no accounting for taste. And there was no predicting it, either, although I tried. I did my best to profile each incoming customer. I picked out the readers I was sure would be interested in River of Dust, but just as often as not, they never even wandered over to my table. Whereas the ones who seemed least likely to engage with me ended up eventually buying a copy.

That evening when I got back home, exhausted and exhilarated from my efforts, I told my high school-aged son that I’d sat at a table in Barnes & Noble for three hours and talked to strangers. For some reason, he took that moment as an opportunity to mention that he would never be interested in work that involved sitting at a desk all day. I said that seemed like an overly simple way to decide what kind of work to pursue in life. Think of all the jobs that precludes, I argued: no reading, writing, computing, teaching, being a professor or a banker (not that anyone in our family has done anything remotely that practical); in other words, no white collar work at all. None of that.

Right, he said, I know.

You know? How do you know?

Because, he said, that’s who I am.

All day I’d been trying to wrap my mind around the business of what we like and why we like it. Who we choose to be when we walk through the doors of a bookstore and make our selections. How we stake our claims and show our interests, our passions, and conversely, how we know what does not interest us at all. Why we either veer towards the table or away from it. Perhaps it’s as simple as that’s who we are. And apparently, the number one lesson in salesmanship, parenting, and even in writing is to be OK with that.

River of Dust, I know with great certainty, is not only the type of book I like to read, but precisely the book I wanted to write.