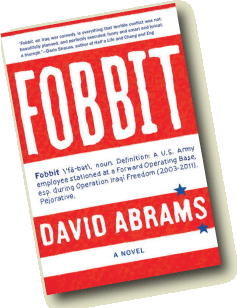

David Abrams’ debut novel about the Iraq War, Fobbit, was named a New York Times Notable Book of 2012 and a Best Book of 2012 by Paste Magazine, St. Louis Post-Dispatch and Barnes & Noble. It was also featured as part of B&N's Discover Great New Writers program and has received much well-deserved love and attention. But I first came to know David because he is such a kind and encouraging literary citizen. Before River of Dust was published, he invited me to contribute to his blog, The Quivering Pen. I wrote for his “My First Time” column in which writers describe their first experience with success, or failure, in writing and publishing. For someone who is relatively new to the world of publishing himself, David has a way of shepherding the less experienced along with him. Perhaps it's his military past that taught him to think about the whole and not just himself, or perhaps it's because he is a father who has raised three children he calls "the small apple orchard of my eye." But in any case, I'm grateful to him for his support and friendship, and I know that many other authors feel the same way. In this interview, I ask him about his experience before his fame with Fobbit. As you might expect, he encourages aspiring writers to "stick with it and believe in yourself."

VP: Your readers know that you served in Iraq and that your wonderful novel, Fobbit, is set there. But, I’m curious about your background as an aspiring writer before and during that time.

David Abrams’ debut novel about the Iraq War, Fobbit, was named a New York Times Notable Book of 2012 and a Best Book of 2012 by Paste Magazine, St. Louis Post-Dispatch and Barnes & Noble. It was also featured as part of B&N's Discover Great New Writers program and has received much well-deserved love and attention. But I first came to know David because he is such a kind and encouraging literary citizen. Before River of Dust was published, he invited me to contribute to his blog, The Quivering Pen. I wrote for his “My First Time” column in which writers describe their first experience with success, or failure, in writing and publishing. For someone who is relatively new to the world of publishing himself, David has a way of shepherding the less experienced along with him. Perhaps it's his military past that taught him to think about the whole and not just himself, or perhaps it's because he is a father who has raised three children he calls "the small apple orchard of my eye." But in any case, I'm grateful to him for his support and friendship, and I know that many other authors feel the same way. In this interview, I ask him about his experience before his fame with Fobbit. As you might expect, he encourages aspiring writers to "stick with it and believe in yourself."

VP: Your readers know that you served in Iraq and that your wonderful novel, Fobbit, is set there. But, I’m curious about your background as an aspiring writer before and during that time.

DA: I like to tell people I was born a writer, not a soldier. Military aspirations were the farthest thing from my mind in the mid-1980s when I joined the Army. I was the proverbial 98-pound weakling, timid, preferred the solitude of books, that sort of thing. At the time, I had a bachelor’s degree in English, a rewarding (if stressful) job as a reporter for a newspaper in Montana, and a couple dozen poems and short stories published in literary magazines with microscopic readerships. I was convinced that, given enough time and circumstances, I could write the next Great American Novel. Such are the pathetic dreams of young, struggling writers. I had ambition, but I also had student loan debt, grocery bills, and a third child on the way. So I joined the Army and was soon indoctrinated into the world of straitjacketed writing for the military. For the first years, I had a lot of fun writing feature stories for the military base newspapers—writing which tapped into my creativity—but it wasn’t long before I was confined to drier writing for reports and technical journals. I compiled training plans and got really good at doing PowerPoint presentations. All this time, in my off-duty hours, I continued to work on my fiction—stories that were deeply influenced by Raymond Carver, John Updike and Flannery O’Connor. I got a lucky break when one of them was published in Esquire but that was about as big as it got back in those days. I earned my MFA from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks while I was working full-time in the Army, squeezing intense writing jags on my thesis between field training exercises in sub-zero weather. In a way, I always felt like my job in the Army was my “sideline” and that writing was my real career. Such was the state of my life in 2005 when I deployed to Iraq with the 3rd Infantry Division. I was, in a way, primed to write something like Fobbit.

VP: I saw in another interview that you had correspondence with your agent while over there. You sent him pieces of writing about your experience. For many writers, getting that first agent can be a huge challenge and a dream-come-true when it happens. We all want to have a literary partner and hope that our agent will become that person. It’s lovely to imagine you sending off your writing to your agent while in Iraq. Can you tell us how that came about? And how working with that person helped shape the book you came to write?

DA: First of all, I need to send out a song of praise for Nat Sobel. As an agent, he had faith in me for nearly six years while I was working on Fobbit. It’s incredible to think he kept me as a client for all that time without having anything in hand to sell. It’s kind of a touching love story, actually. As soon as I arrived in the combat zone, I started keeping a journal. It was a creative record of everything I saw, heard, experienced—I just poured everything into it in a daily brain-dump. At one point, I sent a few of those journal entries to my friend (and now Dzanc Books publisher) Dan Wickett. He posted my Baghdad diary to his blog, Emerging Writers Network. Nat Sobel, legendary agent of Sobel-Weber, happened to read what I wrote and contacted Dan who then played match-maker. So, picture me there in that internet café on Camp Liberty after a long day at work, opening up my email, and seeing a message from Nat Sobel saying he was interested in my work. My head immediately inflated to the size of a hot-air balloon and I went around strutting like a cock-of-the-walk. I had a literary agent! Life was good, I immediately felt bullet-proof there in that combat zone. Surely no harm could come to me now that my writing career was finally on its way. Nat and I continued to correspond with each other that year. He was the one who planted the seed of Fobbit in my head. Early on, we both saw that writing a straight memoir about my time in Baghdad wouldn’t add much to an already-overpopulated field of Iraq War memoirs. Near the end of my tour, Nat wrote to me: “I've come to believe that only in fiction will this insane war finally reach an American reading public.” I went back to my trailer that night and started noodling around characters invented whole cloth out of my imagination, placing them in some real-life situations with which I was familiar.

VP: So did you write Fobbit while there or when you returned? I’m curious when and how you had the time to work it and how long it took you to write? Would you say that yours was a straight path to publication or were there hairpin turns along the way?

DA: As I mentioned, Fobbit grew organically out of my journal—like a new green shoot sprouting out of a tree limb—so in one sense, the novel started the day I set foot on Iraqi soil. While other soldiers went back to their “hooches”—their trailers and tents—after work and played Xbox or cleaned their weapons or hung out with members of the opposite sex, I went back to my room and wrote for two to three hours. It was good therapy—that and reading a crapload of books that year—everyone from Elmore Leonard to Cervantes. I stole my writing time in snatches, little sips of time during the day and late at night. Fobbit the narrative didn’t really get going until the very end of my time in Iraq, and I really went to town on it once I returned stateside. Like most of my writing projects, it had its ebbs and flows, periods of time when it languished and I made sorry excuses for not sitting down at the keyboard on a daily basis. For the most part, though, I think Fobbit’s path to publication was pretty straight. Once Nat and I were happy with the final draft and he started shopping it around, it went pretty quickly, at least by my standards. Grove/Atlantic came back with an offer less than a month after Nat sent it out, which is pretty amazing to me.

VP: I can’t resist asking the question that must come at all writers who write about war: do you, like Hemingway, feel that people need to have major life experiences in order to have something to write about? Or, do you agree with Eudora Welty that, “a quiet life can be a daring life as well, for all serious daring starts from within?”

DA: Would I have written Fobbit if I hadn’t actually gone to Iraq and been immersed in the day-to-day reality of war? Probably, but it wouldn’t be the same book. It wouldn’t have that intensity of truth. I would have been guessing (and probably guessing wrong) at the things I actually experienced. That being said, I just spent 20 years working on a novel about a midget who gets a job as a stuntman in 1940s Hollywood. I’ve never been a midget, never lived in the 1940s, and only spent two days in Hollywood as a tourist—but somehow I was able to pull it off. On the whole, my life has been pretty boring, bland as a cardboard cutout—no running of bulls, no deep-sea fishing off the coast of Cuba, no hairy-chested Hemingway adventures—but I do have plenty of unexplored worlds in my head. That’s where I find an interesting life to write about.

VP: What advice do you have for aspiring writers who strive to have their debut novel published?

DA: It took me nearly 30 years to get a novel published, so I suppose saying “Stick with it and believe in yourself” might not be what most beginning writers want to hear. I can certainly understand the desire to have something published now and not decades from now. Lord knows that was my dream and frustration for 30 years. In all that time, though, I never stopped believing someone somewhere would be interested in my writing—it couldn’t be that bad, could it? You have to have faith in your work—especially in those dark, lonely days when it seems like no one else does. Eventually, if you keep writing and keep pushing against the tide of negativity and rejection, something will happen. And if it doesn’t, what’s the worst that will have happened? You’ll have brought some beautiful words into the world, even if they’re only beautiful to you.