Happiness is in. Advice on how to achieve it fills volumes on bookstore shelves. Some of these books rely on scientific research. Others refer to the wisdom of the ages and sacred texts. They urge us to pursue ambitious life goals. Or jump off the hamster wheel and ditch our career goals entirely and relish simple pleasures instead: eating well, breathing deeply, meditation and exercise. Hunker down at home with those we love, or embark on daring adventures to distant shores. Face our fears. Do our bucket lists. Ditch all lists. Give up. Give in. Give back. Don’t give a fuck. Or fuck a lot. All in the pursuit of happiness.

The titles alone promise verifiably achievable outcomes: The Happiness Curve. The Happiness Project. The Happiness Hypothesis. 10% Happier. While others offer a looser, more free-form approach: Stumbling on Happiness. The Art of Happiness. Authentic Happiness. Each promises something hopeful, lasting and, most of all, real.

And yet, in my way of thinking, happiness can best be found outside the realm of reality. Let me explain. Over the course of more decades than I’d like to admit, I have reliably found happiness through reading and writing fiction. I’m convinced that happiness is unconsciously absorbed into the bloodstream through words—words that transport us into the imagined hearts and minds of others. Fiction offers a window into the human soul and psyche. If done well, the inner lives of characters remind us of what it means to be human.

What we read doesn’t necessarily need to be happy. The literature I was raised on reveled in quite the opposite. Madame Bovary is a tragedy. Anna Karenina, a disastrous tale. In Chekov, you can search a long time for a happy ending because the characters are so flawed. They are vain and puffed up with self-importance, blind to their own follies, crippled by unrequited love, and often just plain silly. In other words, they are human.

Reading about such weak and lovelorn characters has helped me all my life to stay alert to my own flaws. The more current characters in A Little Life swim in their own unhappiness, while in The Sympathizer the protagonist remains stoical in the face of his life’s conundrums. Great literature of every era explores human imperfection and sorrow, helping us to recognize that our own lives are more balanced by comparison.

Any reader would understand the recent scientific study that proved that empathy is increased by reading fiction. That seems like a no-brainer to the bookish set. It went without saying that reading made our lives richer; our ability to love deeper; our understanding of the human condition more profound. It feels silly articulating what my parent’s generation and all the generations before took for granted. But in today’s climate, while so many other voices are screaming for attention, it’s worth remembering that reading a good work of fiction is not only not a waste of time, but a deeply human activity. One that, through the decades, has helped us to know who we are.

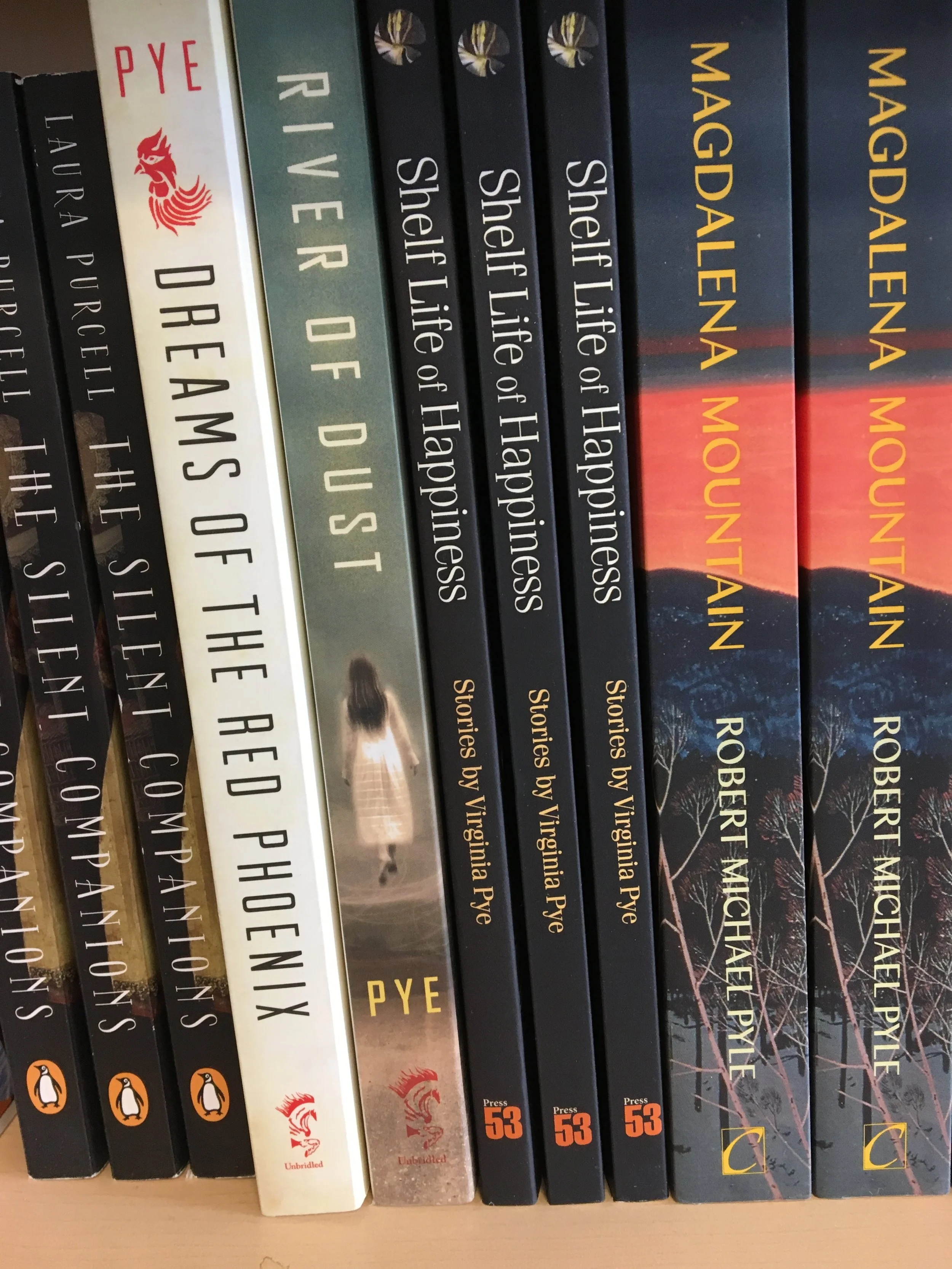

As a writer, penning fiction has also helped me to know myself and, therefore, as the philosophers opined, to know happiness. The stories in my collection, Shelf Life of Happiness, are about characters of widely different ages and genders, told in voices quite unlike my own. They aren’t autobiographical, but like many fiction writers, I transform what I have experienced into imagined truth. This process of unconsciously inventing from life has helped me “process” painful moments. When something is bothering me, I make up stories to tame it and ultimately let it go.

At a rocky moment in my marriage, I traveled to Rome with my husband and two children and walked on the literally rocky terrain of the Forum, teetering on the edge of marital discord and even rupture. Not long after our return, I sat at my desk and in my story, Crying in Italian, I created an unhinged wife and mother who wanders off from her family and is seduced by the sight of young lovers in the Roman ruins. She longs to be free of the constraints of her life—jettisoning her husband and children for what she imagines is a more passionate existence. She literally stumbles and, without giving away the ending, finds herself on the precipice. The writing of that story helped me with my footing in my marriage and my life back home. It didn’t solve my problems, but by imagining a woman who risks all, I didn’t have to. And dear reader, I’m happily married to this day.

Writing my long story Her Mother’s Garden, which was also inspired by real events, helped me through the loss of my parents. Some years ago, they sold the house where I had grown up and it was subsequently torn down. But worse, the stunning garden my mother had cultivated for over forty years was bulldozed. Rhododendrons heavy with magenta blooms, pink climbing roses crowning an arbor, royal blue iris standing at attention beside a shaded pool where golden carp circled at dusk were all relegated to memory. Then came the illnesses, the falls, the strokes, and finally, death, first my father and then my mother. Like other members of my family, I tried my best to process this period of sorrow. But only by writing a story about a daughter’s attachment to her mother’s garden, and the sad experience of watching her parents age and her childhood recede, was I able to move forward.

Writing this story hollowed me out and left me feeling spent, but the surprising end helped me to stand again on my own two feet. After many drafts, I came to realize that the daughter needed something specific to happen to make her understand she must leave the haunted landscape of her childhood. Nudged off the garden path, she finally steps outside the cloistered loveliness of her mother’s garden—as did I.

After finishing that story, I felt quite different, not only about my past, but my future. I hope readers will feel similarly when they read it. A good work of fiction should leave us better prepared for what we face off the page—not in a prescriptive way, but by enlarging our human understanding. The tales we read, and those we write, should be rich with a dark, nourishing soil—to continue the garden metaphor—that allows us to thrive and grow upward into sunlight.

According to Professor Laurie Santos in her PSYC 157: Psychology and the Good Life—the most popular class in the history of Yale University—genetics shape roughly 50 percent of our chances for happiness, while ten percent is dictated by circumstances beyond our control. But the final 40 percent is determined by our thoughts and attitudes. Novels and stories that infuse themselves into our consciousness and reshape how we see the world can tip that crucial 40 percent towards happiness.

Though, in the end, perhaps simple happiness is one of the least rewards of reading and writing fiction. A deeper, more profound understanding of life through literature can outweigh all of this year’s self-help bestsellers promising easy rewards. For as we go in search of greater meaning in life, we can do no better than to open a good book of fiction and let ourselves remember who we are at our most complex and real.